Kelli Bippert

kelli.bippert@utsa.edu

Dennis Davis

dennis.davis@utsa.edu

Margaret Rose Hilburn

maggie.r.arnold@gmail.com

Jennifer D. Hooper

jennifer.hooper@utsa.edu

Deepti Kharod

deepti.kharod@utsa.edu

Cinthia Rodriguez

cinthia.rodriguez@utsa.edu

Rebecca Stortz

rebecca.stortz@utsa.edu

San Antonio, Texas, USA

The University of Texas at San Antonio

Abstract

This article utilizes sociocultural and socio-constructivist learning theories to analyze incidents of learning, and by extension teaching, in six different popular media selections. The authors describe their shared theoretical framework and the nature of the original analyses, which were completed as part of a doctoral course assignment. Each of the six excerpts is then described and discussed employing unique theoretical perspectives. The use of popular culture as the context for examining learning and teaching provides a space untethered from traditional notions of schooling through which typically accepted assumptions about pedagogy are revealed, re-examined, and reframed.

Keywords

Sociocultural, Socio-constructivist, Learning, Teaching, Popular Culture, Media Studies, Pedagogy, Education, Communities of Practice

In this article, we describe an innovative pedagogy used in a higher education setting to facilitate reflection and unpacking of a complex construct that often goes unexamined in our field. We (the authors) are doctoral students and a faculty member in an interdisciplinary PhD program in learning and teaching, and we all identify as current and prospective teacher educators dedicated to the development of high quality and critically conscious PK-12 teachers. Our doctoral program intentionally highlights the importance of interdisciplinary inquiry as a stance and a methodology for approaching complex problems in educational scholarship (Repko, Klein). Because of the interdisciplinary nature of this program, our departmental membership represents a community of practice (Lave and Wenger) that intersects different educational and teaching backgrounds—art, literacy, early childhood, educational technology, mathematics, and science education—each with its own socio-historically developed commitments to different theories and perspectives on learning and teaching.

Given the variations across our individual perspectives and our goal of finding common understandings that transcend disciplinary boundaries, we have found it useful in our shared conversations about what it means to learn—and by extension, to teach—to identify common accounts of learning/teaching in popular media. Popular culture, including television, literature, and film media, often portrays a snapshot of our world through compelling fictional and historical characters (Storey). In this article, we leverage the potential of popular media to provide common spaces for counternarratives that problematize the givens of learning and teaching.

Traditional accounts of learning/teaching are often corrupted by the assembly-line structures of contemporary schooling (Rogoff, Paradise, Arauz et al.; Sawyer) and the ideological perspectives built into standards and curriculum surrounding knowledge (Luke 13). In this article, we assume that examples of learning in popular media, particularly those that are untethered from traditional schooling, can be illustrative cases for re-conceptualizing what it means to learn and teach. Beyond providing entertainment, popular culture is a space in which our perceptions and taken-for-granted assumptions about the world are shaped (Grossberg 94). The pedagogy described in this article was designed to help us “[turn] a skeptical eye toward assumptions, ideas that have become ‘naturalized,’ notions that are no longer questioned” (Pennycook 7). This “problematization of the given” is an important part of our ongoing work to re-configure our own conceptualizations of learning/teaching so that we can be more effective and critically conscious in our work with prospective teachers. The analyses detailed here center on the following questions: In what ways do the fictional worlds within popular culture create a portal for analyzing the ways that learning and teaching occur in out-of-school contexts; and How might these analyses offer new understandings about learning/teaching that can enrich the way we model and discuss learning with future K-12 teachers in higher education?

The analyses detailed here began as part of a doctoral course, titled Socio-constructivist and Cognitivist Perspectives on Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching, focused on socio-culturalist, socio-constructivist, and cognitivist theories as related to formal and informal learning and teaching. The primary assignment in this course was an ongoing inquiry in which we applied these theories to analyze learning and teaching events found in popular culture. Each student-author identified a “narrative of learning” in popular media, defined as an event or series of events in which someone is observed learning or changing, either incidentally or as a result of intentional teaching. Each individual student-author’s contribution featured different modes and theories that encompassed their learning and teaching event. The power of analyzing learning and teaching through six different socio-cultural lenses helped solidify these doctoral students’ understanding of how sociocultural learning and teaching occur in the everyday.

The analysis in this paper is undergirded by socio-cultural and socio-constructivist perspectives that establish learning as an interactive relationship between the individual and the social environment. Several general themes can be extracted from these two theories regarding learning and teaching. One claim is that all learning exists within the social setting and is internalized by the individual and then transmitted back to society (Vygotsky). A second notion is that learning requires the use of cultural tools (Vygotsky; Wertsch), both physical and abstract, which are inseparable from the individual. More so, in order for learning to occur, individuals must be active participants in their situated environment (Lave and Wenger).

Principally, learning is seen as an interactional process, where the learner is in a constant reciprocal relationship with the environment. These interactions cause the learner to act and react to socially-defined practices by adapting, engaging, contributing, and using past experiences (Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds; Cobb). These actions change the learner and the community in various ways. First, the learner evolves, by developing past practices and making new contributions. Second, the transformation of the learner affects the situated setting, which can lead to changes in cultural norms, tools, and practices. Consequently, this interplay between learner and society causes learning shifts that are constantly impacting both the individual and their community (Lave and Wenger 51; Wenger 227). This leads to the notion that learning and teaching form a continuous and transformative cycle; “a process results in a product that in turn influences subsequent processes” (Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds 180).

However, these ideas produce only a general viewpoint of the learning and teaching process. Although there are many social learning theories that seek to further explain these elements, there is an ongoing debate about what learning is (Bruner; Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds), how it develops (Greeno, Collins, and Resnik; John-Steiner and Mahn), and how varying perspectives on learning might inform the practice of teaching (Sawyer). Because social learning views argue that the learner is inseparable from the environment and cultural tools, examining novice learners in their authentic setting is critical. It is important to consider how new members experience their environment, interact with new cultural tools, and seek support from other community members. In this sense, popular culture provides a unique space to examine a range of diverse learning and teaching scenarios.

The Process

We engaged in a three-layered process that helped question, reframe, and clarify our understandings about social perspectives of learning and teaching. The process began with unpacking various theories in the context of a doctoral course, then using those understandings to undertake an individual analysis, and finally collaborating with our peers to uncover shared findings to write this article.

First, as authors of our individual analyses, we began with certain shared premises grounded in sociocultural theory. Learning and teaching were understood as mutually transformative practices situated in a common space (Lave and Wenger; Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds). The space provided opportunities for learning and feedback. The learning process also relied on the use of tools, both physical objects and strategies or practices. Finally, the learning resulted in mastery, making what was internal to the learner visible to the community.

From there, we employed unique lenses to view what was being learned, how it was learned and evidenced, and what was the role of explicit teaching in that process. Our experiences as classroom teachers in varied school settings informed these decisions, as did our different disciplines, and personal preferences regarding popular media.

Finally, the decision to collaborate in this joint analysis emerged from a shared value of interdisciplinarity. The process of reading each other’s original papers, exploring common findings, and appreciating varied viewpoints has uncovered understandings that run deeper than a typical co-authoring experience. We have gained insight as to how art, literacy, math, and science intersect with each other, and with early childhood, elementary, secondary, and undergraduate learning and teaching. These common grounds are not simply in the space of lessons or learning activities, but more fundamentally in terms of how we view our students, ourselves as students and teachers, and the very meanings of learning and teaching.

Findings from Individual Analyses

This study aims to analyze learning and teaching episodes found within popular media. Using excerpts from Orange is the New Black, The Walking Dead, Megamind, Sherlock, Exit Through the Giftshop, and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the student-authors follow novice learners as they interact with their respective environments.

In the popular Netflix series, Orange is the New Black (http://www.netflix.com/WiMovie/70242311), Piper Chapman, a co-owner of an artisanal soap-making business, is living in an upper-middle class neighborhood. In the initial episode, Chapman self-surrenders at Litchfield Women’s Prison due to an international drug smuggling crime she committed ten years prior. On her first day, Chapman accidentally insults Red, the veteran kitchen manager, and instantly loses her food privileges. Consequently, she begins a series of problem-solving events to amend her relationship with Red. In order to survive, Chapman has to learn the hidden rules, overcome obstacles, and earn a respected place in the prison community. The social learning concept articulated in Rom Harré’s Vygotsky Space model was utilized to understand Piper Chapman’s interactions as she learned to adapt, participate, and contribute in the established prison environment in the first episodes of the series.

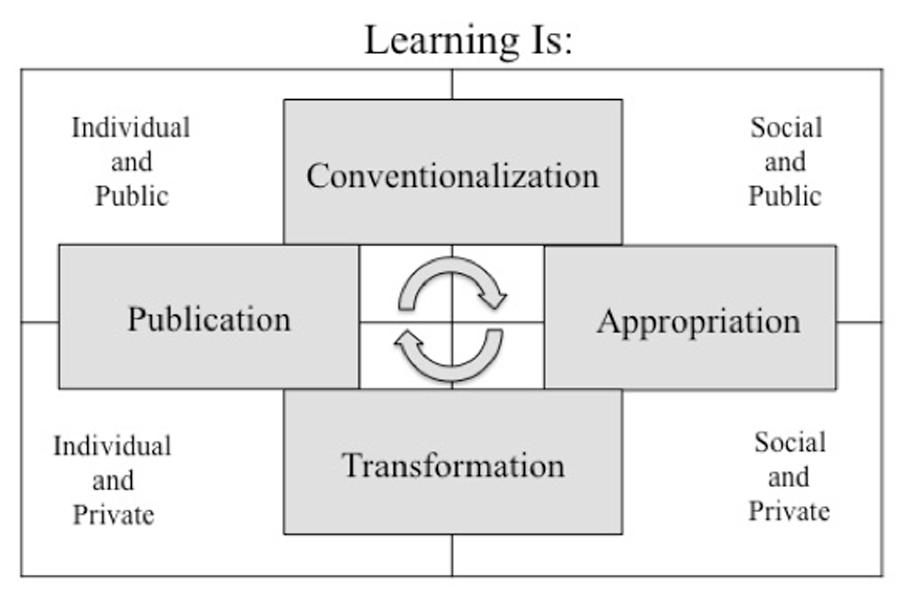

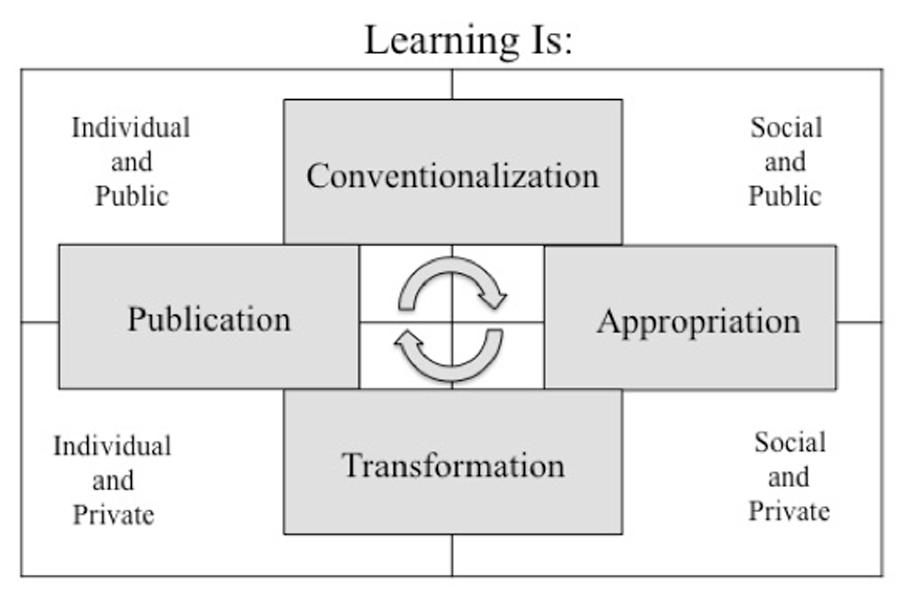

The Vygotsky Space model explores how learners interact within their social environment, internalize learning, and create contributions. The theory states that the learner is always situated within two dimensions: the public/private and the individual/social. Furthermore, it claims that these two dimensions interact with each other to form four quadrants of learning (Gavelek and Raphael 187). As learners transition through the quadrants, they engage in the developmental activities of Appropriation, Transformation, Publication, and Conventionalization (see Table 1, adapted from Gavelek and Raphael).

Table 1 Dimensions of Learning

During Appropriation, knowledge is social and public, allowing the learner to acquire it. In the Transformation phase, the learner’s appropriated knowledge is transformed into his or her own, yielding changes in the individual. These changes allow the learner to make visible contributions to the environment in the form of Publications. The acceptance of these contributions by society is seen as Conventionalization. Thus, the product is an ongoing cycle where the learner interacts within various private and social sectors that ultimately alter the individual and social context.

The Vygotsky Space assists in understanding the process of learning by examining both individual and social changes that occur throughout the four quadrants. This theoretical lens was employed to examine the actions of Piper Chapman during her initial stay at Litchfield Women’s Prison. Several key findings emerged from the analysis.

First, it was evident that Chapman’s initial lack of social knowledge in the prison environment led to immediate mistakes that changed her course of action. This created a need for specific knowledge, which placed her in various developmental opportunities. These included learning the bartering system and understanding the prison’s social hierarchy in order to obtain and exchange goods. A second finding was that cultural tools restricted and supported the learner during Appropriation.When the learner encountered physical items, they initially posed obstacles because they were used differently in the prison setting. However, as Chapman practiced using the items through trial-and-error, the tools became supporting elements of learning. Lastly, the examination found that the Transformation and Publication of cultural tools by the new member were substantial in gaining confidence, power, and acceptance. By creating and introducing tools, Chapman showed the community that she had mastered useful practices. The prisoners acknowledged Chapman’s actions and accepted her Publications. An example was apparent when Chapman learned to use the bartering system and gathered items to create a therapeutic lotion that she presented to Red. As a result, Chapman regained her food privileges and the respect of the senior inmates.

From this analysis it is evident that the new learner’s lack of initial social knowledge placed her in specific developmental opportunities. These led to individual contributions in the form of publicized practices and newly created cultural tools, transforming both the individual and her social context.

The next analysis focuses on The Walking Dead (http://www.amctv.com/shows/the-walking-dead), the AMC television series about a group of people trying to survive a zombie apocalypse. The presence of the walkers, or zombies, is the driving force behind the group dynamics and the reason their society becomes focused on survival. This analysis examines the motivations between Shane, an established leader in the survivor community and Andrea, a member with less authority in the community with a sociocultural lens. Shane teaches Andrea through a scaffolding approach, enabling him to assess her learning and motivation. (See Neely for another analysis of this same event.

This analysis assumes that the standards and values that motivate individual learning are socially constructed (Hickey and Zuiker 288). Learning and behavior, as well as the society and culture in which they occur, are the forces that drive individual motivation. It is also understood that individuals have different motivations for learning. For example, Andrea is motivated to learn how to shoot so she can protect others and prove herself as a valued member of her new community; however, her ability to handle a gun has been questioned. Shane on the other hand has a different motivation. As one of the leaders, it benefits him to train others for two reasons: first, he does not have to work as hard shooting the walkers because others are helping him; and second, he does not have to continually watch over others while shooting the walkers.

This analysis focuses on three excerpts from Episode 6 in Season 2 that depict motivation through scaffolding. The intrinsic motivation felt by Andrea and Shane emphasizes the importance of learning; it also is essential to the human need for survival. Feedback is essential for one’s sense of control, is vital to intrinsic motivation, and improves learning. Unlike the others, Andrea bypasses the beginner tasks in her training and challenges herself to shoot at a harder target found in the “No Trespassing” sign. In response, Shane challenges her to the advanced class. This challenge to prove herself piques Andrea’s interest and increases her motivation. It also capitalizes on Shane’s motivation because he can nurture Andrea’s skills and help him reach his own goal of having more trained individuals in the community.

In this particular scenario, Shane is badgering Andrea to shoot a moving target, trying to simulate a stressful interaction with a walker. After many failed attempts, her motivation begins to diminish. Illustrated by Madeline Hunter’s observation that degree of success is an important variable in motivation, Andrea’s low degree of success leads to low motivation. Eventually, as a result of her failure and Shane’s negative feedback, she quits and walks off.

By the end of the episode, Andrea’s and Shane’s different personal motivations intersect in pursuit of a common goal of survival. Thus, the urgency to shoot the walkers provides a common motivation for learning and teaching. As Yrjö Engeström explains from his situated learning perspective, the motivation to learn stems from participation in culturally valued, collaborated practices in which something useful is produced (141). Barohny Eun states that when you scaffold the learning process like Shane does, the learner (Andrea) needs to have each skill be both solid and well-embedded (410). It is these scaffolding situations that will help Andrea be able to utilize her gun, effectively utilizing the skills learned in prior situations. When faced with walkers, Andrea is able to apply her learning in a real life situation; she is more motivated and committed in her learning process.

The third individual analysis examines issues surrounding learner identity in the DreamWorks movie Megamind (http://www.megamind.com/). What forces shape a person into becoming a superhero? What forces shape others in becoming villains? The film Megamind acts as a social commentary, addressing the formation of identities by peer groups and the larger society. Through his experiences with society, the film’s protagonist, Megamind, learns as a child to accept villainy as his destiny, resolving to become the “baddest boy of them all.”

Two theories were addressed in the analysis of the opening scene: identity theory and positioning theory. According to James Paul Gee (“Identity as an Analytic Tool”), identity is described as the way a person is seen, a type of person, in society. A person’s nature-identity describes his or her physical traits and other aspects of the person that have been shaped by forces outside of the individual’s control. The institution-identity comprises the person’s official identity within society and his or her related powers and rights. Discourse-identity is shaped by the interactions that take place between the individual and others in the community. It reflects the individual’s relationship with others and is shaped by interactions within society. The fourth type of identity is the affinity-identity related to a person’s involvement in particular groups based on similar interests or activities. An individual’s position in society, and the power associated with it, is directly related to that person’s view of self (Davies and Harré 6). Of course, a person may choose to write his or her own “storyline,” pushing to increase rights and duties within the larger society. According to Rom Harré (“Positioning Theory” 3), positioning theory describes how rights and duties are distributed, change, and challenged over the course of a lifetime.

The film’s exposition was divided into four major parts, each occurring where the account of Megamind’s young life made major shifts. The exposition of the film Megamind was analyzed using discourse analysis (Gee, “How to do Discourse Analysis”). Each utterance within these parts was analyzed using Gee’s four types of learner identity (Gee, “Identity as an Analytic Tool” 100) and the expansion or retraction of rights and duty related to positioning (Harré, “Positioning Theory” 3).

Four patterns emerged based on the content of the exposition. In part one, the most commonly coded example of identity was nature-identity; at this point the exposition, which displayed Megamind’s earliest memories, showed very limited social interactions. In part two, institution-identity and reduction of rights were coded most frequently as he makes his home among prison inmates. In the third part, Megamind begins school and interacts with his teacher and classmates, and discourse-identity was coded more than in any other part of the transcription. The consequences of his perceived bad behavior result in his removal from much of the social interactions that occur in the classroom, limiting his rights and duties. Finally, part four of the exposition features the main character continuing the trend of negative discourse-identity formations and reduction of rights, as he chooses to push against social norms and positioning, creating his own storyline, starring Megamind as the “baddest boy of them all.”

By closely analyzing student, teacher, and peer interactions with at-risk children, we can gain better insights to reasons that many children push against norms set in the classroom. Megamind’s experiences in school could describe situations in which many marginalized children find themselves. Megamind, the protagonist in this film, is very much like many students who attempt to participate in school learning community, yet for various reasons fail to thrive as members of their learning environment. Be it intentional or not, the writers of the animated film Megamind described the very essence of how and why many children struggle in the traditional classroom.

The fourth vignette investigates identity formation in a different context. Over the course of the three seasons of BBC’s Sherlock (http://www.bbcamerica.com/sherlock/), John Watson develops from a damaged survivor of the Afghanistan war to a fully-realized, deductive-reasoning, consulting detective’s assistant. He forms and recognizes this new identity through his social interactions and experiences of working alongside Sherlock Holmes as they investigate and solve crimes at various locations within a period of three years. Watson’s cognitive, social, cultural, and psychological identities undergo a transformation that would be impossible without these social experiences. More than just the building of ideas from within the mind, learning for Watson must be analyzed from within the larger context of his place in society.

George Herbert Mead’s seminal work on identity formation stresses the impossibility of separating the self from the society in which it is formed. He further transfers the concept of communication between two or more people into an internal conversation within the individual. The person therefore becomes his own inner community. This concept, which he calls abstraction, cannot be the only interaction within a society, of course, but it helps to explain how identity formation becomes an internalized process, one that ultimately requires full participation of the individual.

Sheldon Stryker further explores the concept of identity theory by refining Mead’s work into a simple model explained as “society shapes self shapes social behavior” (Stryker 28). He likens identity to a mosaic, blending bits and pieces of social interaction to form a complete whole. It is relatively patterned, yet crosses new boundaries as new social interactions take place. Stryker finds that a shared meaning of a concept or idea provided the commonality to link identity and behavior (31). The practices within the identity and social community, and the common usage of the meaning, provide an extension of how identity is created.

In the beginning of the series, John Watson is a returning soldier and a doctor from the Afghanistan war, clearly affected by the violence and trauma of his experiences there. In therapy for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, his therapist has advised him to stay calm, get involved in “normal” society, and reintegrate himself with civilians and a quiet life. He has difficulty reckoning his inner desire to experience more danger and violence with the socially accepted reaction that he should be feeling. Scenes from the first season emphasize this dissonance, showcasing situations where Watson fluctuates between settling down in the life of a clinical doctor and relishing the high energy of detective work. His time is ripe for learning a new life, one where he is both in control and in enough danger to satisfy his needs. This new community Sherlock Holmes provides comes at the perfect time for Watson’s emerging identity.

By season three, Watson proves himself a fully-formed identity as an investigator. One key scene in the final episode depicts both his skill as an investigator and his mentor’s awareness of these skills. Holmes has been shot and has left clues for Watson to figure out the case, knowing that Watson will be able to separate his emotions from logic and connect the dots, realizing that his own wife is the person who has shot his best friend. If this identity as an investigator had not been fully formed, Watson’s denial of evidence would have hindered his conclusions. The clues he collects, and the conclusions he makes from them, are symbolic of the larger ability to think like an investigator. This ingrained methodology has become a natural practice, one in which Watson engages without conscious thought. Watson’s identity arc corresponds with the narrative arc of the show; while he will continue to grow and develop as an investigator, as all learning continues, he now has ownership of his identity. The social context in which Watson is placed at this time has shifted yet again. A married man, practicing doctor, part-time investigator, this Watson has finally claimed ownership of his new identity.

The next analysis centers on cultural tools and co-construction. The 2010 documentary film, Exit Through the Gift Shop, examines Thierry Guerra’s induction to the secretive community of some of the world’s most famous street artists (http://www.banksyfilm.com). Initially, Guerra is allowed access to the exclusive group under the assumption that he is a documentary filmmaker. However, Guerra is not content with simply standing by as an observer, and through an unintentional apprenticeship, remakes himself into the street artist known as Mr. Brainwash. This analysis of Guerra’s transformation reveals insights about how cultural tools help to scaffold artistic meaning making.

From a social constructivist perspective, cultural products such as language and signs semiotics are considered to mediate our thoughts and mold our reality (Vygotsky). Sign mediated activities include “systems of counting; mnemonic techniques; algebraic symbol systems; works of art; writing; schemes, diagrams, maps and mechanical drawings; all sorts of conventional signs and so on” (Vygotsky 137). These semiotic means are referred to as tools, and it is with the aid of these tools that we construct our knowledge. James Wertsch believes that these cultural tools manipulate human action within the mind and in the world. He emphasizes the importance between the relationship of external cultural tools and their influence of internal processes.

The concept that individuals employ internal cultural tools to make sense of the external world is referred to as co-construction. The mastery of a new concept, skill or tool is the process of internalization. Furthermore, a skill or tool can be appropriated, meaning that it has been used in a unique or individual way. It is through an internal conversation that individuals appropriate and reconstruct their understanding (Harré). Semiotic representations, shaped by and indistinguishable from culture, aid our processes of internalization. Ernest Gombrich (as cited in Cunliffe) situates works of art not only in the mind of the artist, but also within social and cultural contexts. He proposes that artistic ability is not simply a naturally inherited gift, but that symbolic cultural representations, in the form of tradition, influence the work of artists by providing visual cues and critical feedback.

In Exit Through the Gift Shop, the degree to which graffiti culture influenced Guerra’s artistic decision making is extensive. Often, Guerra appropriates the images, style, and artistic approaches that he observed during his time among the street art community. Throughout the film Guerra is able to engage with and observe how expert artists test and refine their practices through the mechanism of corrective feedback. One such example occurs when graffiti artist Space Invader asks Guerra what he thinks of his mosaic, and then later when he seeks Guerra’s help in installing the mosaic on a building.

Though frequently unsuccessful in his initial attempts at art making, Guerra is able to appropriate the strategies of trial and error and corrective feedback to his eventual success. Guerra’s mastery of these tools is evidence of his internalization of the practices and tools of the street artist community. This internal conversation and transformation was instrumental in reconstructing Guerra’s identity from Guerra the documentary filmmaker to Mr. Brainwash, successful street artist.

Finally, although educators frequently conceptualize learning as an intentional product of teaching, an analysis of J.K. Rowling’s book, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, reveals many layers of learning occurring simultaneously, often in the absence of purposeful teaching, and exposes issues of periphery and power (http://harrypotter.scholastic.com). As a new student at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, Harry happens upon the magical Mirror of Erised. His initial interactions are directly with the Mirror, but Harry also learns about its powers from his mentor, Headmaster Dumbledore, before encountering it again in a high-stakes duel with Professor Quirrell (possessed by the evil Voldemort’s spirit).

In their definition of learning, Patricia Alexander, Diane Schallert, and Ralph Reynolds describe it as both “conscious and intentional,” and “tacit and incidental” (178), so learning is continuous (Matusov 338), inevitable (Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds 178), and multifunctional (Davis 105). Teachers and students constantly (but not always consciously) send and receive messages about expectations, socialization, power, and other cultural norms of their community. So, within a single activity, a learner typically experiences several types, or layers, of learning simultaneously. This study analyzes Harry’s learning by what he learns (tool, environment, and identity) and how he learns (incidental or intentional, guided by teacher or learner).

Layers of learning across the what categories is evident when the Mirror drops the Sorcerer’s Stone into Harry’s pocket. Harry gains new understandings about a magical tool (the Mirror), norms of the wizarding world (the Stone’s reflection materializes in his pocket), and his changing identity (from loser in his uncle’s household to hero at Hogwarts). Through this single event, Harry experiences three layers of learning.

Harry also experiences multiple layers in terms of how he learns: intentionally through Dumbledore’s explanation (teacher) and Harry’s following his advice (learner), and incidentally when he experiences the Mirror’s magic. Rowling describes Harry’s reflection twice as changing from “pale and scared-looking” to smiling (208, 292). The first time is when Harry originally encounters the Mirror and sees his reflection surrounded by family; the next is when he encounters the Mirror during his final confrontation with Quirrell/ Voldemort. After the first incident, Prof. Dumbledore suggests that Harry avoid losing himself in the fantasies the Mirror shows him, and Harry decides to do so. Finally, the incidental learning occurs in that Harry accidentally encounters the Mirror in the storeroom before he faces it in a high-stakes situation (assuming that Dumbledore did not mastermind the coincidence).

Power is inherent in educational relationships, with the expectation that a learner’s power increases with greater experience, knowledge, and mastery of craft and culture. Although institutional power rests with teachers (compared to students), Jean Lave and EtienneWenger note that the periphery offers a position of power, too (36). Harry’s mastery of certain spells and tools is not valued or even permitted in his classrooms; however, it is invaluable in actual practice. He remains an outsider, even as a hero, because of his unfamiliarity with wizarding culture as well as his own personality and choices. The Mirror episodes afford opportunities to reframe learning, from a planned activity to a continuous, multi-layered experience. Harry’s experiences also highlight the power that a peripheral position can confer in a community of practice.

Uncovering the Givens and Identifying Tensions

While each of these examinations uses a distinct lens in addition to the shared social learning theories, looking across these six vignettes brings further insight regarding teaching and learning.

Through our reflections on the process of examining cases of learning/teaching in popular media, we have identified two broad implications of this work: 1) helping us see learning/teaching more clearly, around the boundaries of what we were accustomed to seeing; and 2) identifying dialectic tensions that expand the complexity of our thinking about learning.

As an example of the “givens” in the field of education that we were able to examine more deeply as a result of our analyses of out-of-school learning as represented in popular media, we offer the following list of assumptions, developed through our class discussions, that are often played out in typical classroom practice in K-12 settings and required of beginning teachers in a typical education program as evidence of readiness for leading a classroom:

- Assumption of designed intentionality: there has to be an observable, measurable objective, written with a clear verb and statement of evidence

- Assumption of observable and instant mastery: the lesson is successful if all (or most) students at the end of the lesson have “mastered” the objective

- Assumption of tangible evidence: Mastery is almost always documented through the creation of tangible artifacts (writing), even to the point where some things are written (or copied) simply for the purpose of creating this artifact when they could be more efficiently and authentically accomplished through talk or other intangible practices

- Assumption of active engagement: the lesson is successful if all students look busy

- Assumption of structure: there is an expected architecture to the lesson sequence and the lesson is successful if all components are performed for the appropriate amount of time in the appropriate order

- Assumption of tidiness: the lesson is successful if it is tidy and compliant such that disruptions or meanderings from the architecture are discouraged and instances of dissonance or conceptual struggle are deemed indicators of bad teaching

It is certainly beyond the scope of this article to argue that these normalized practices are universally incorrect or ineffective, and we do not claim to dispute accumulated evidence for the need for these and other features of standards-based and data-driven instruction. Our point is simply that part of our work as interdisciplinary scholars who hope to extend our quality as teacher educators is to engage in thoughtful critique of these and other givens of learning/teaching that are rarely questioned or even noticed because they are assumed to be true and natural. Each of these ritualized practices rests on assumptions about how learning occurs and what is worth learning. Our cases of learning in popular media give us a shared context for examining learning in a way that is less corrupted by these practices so that we can engage in what Gee calls critical learning: learning to notice, critique, rearrange the design features built into a semiotic domain (Video Games 25).

Our reflection on these cases also helped us develop a list of tensions or dialectics—two seemingly opposing states that cannot be easily collapsed into each other or resolved—related to learning that expand the way we now talk about learning with colleagues and students. These four tensions are summarized below.

Coercion/volition is the first tension we identified. Our cases show examples of learners learning through participation in communities they have chosen to affiliate with (or have allowed themselves to be recruited into). At the same time, though, the learners are compelled or coerced to follow accepted pathways of access and to learn a prescribed sequence of practices. There are both individual agency and external authority driving their participation in these communities.

The second tension we identified is labeled replication/innovation. Learners who gain exclusive levels of centrality in their communities do so through the appropriation of tools and practices. which allows them to push the limits of how these tools/practices can be used (Lave and Wenger; Wertsch). Members do not just replicate the conventionalized practices of a community (Gavelek and Raphael). They actually “own” them and transform them, spitting back the transformed forms into the community so that others can also internalize the novelties they have helped build. It is important to point out, though, that replication is not totally removed from the process. There is some degree of absorption of pre-existing practices, things that make the community a community. A learner has to enter into social contracts with other members of the community, and some of these contracts involve the adoption of cultural models, tools, practices, and so forth that bind the community together.

Our cases also reveal a whole/part tension. Most of our cases center on individuals who are recruited into the practices they are hoping to learn in such a way that they are able to experience (at the very least, observe) the whole practice from the very beginning of their community affiliation. Their immersion in the whole practice is what makes their learning possible; it allows them to imagine a possible future in which they are doing all the parts of the process (Gee, Video Games; Lave and Wenger). At the same time, though, a new member in a community cannot do all the parts of the practice instantly (not well, at least). There is a partitioning or sequestration of the content that happens (sometimes incidentally, and sometimes in institutionalized ways). The learner gets access to the whole thing but also works through parts of the whole thing in the sequence that has been deemed acceptable by old-timers in the community (Lave and Wenger).

The final tension exposed in our analysis, intentional/inevitable, reflects our understanding that learning can be launched by an intentional act of teaching or can happen incidentally through interactions or experiences in which there is no nameable agent who purposely fills a teacher role. Furthermore, even when there is intentional teaching, there is always (inevitably) some learning that occurs that is not intended (Alexander, Schallert, and Reynolds). This can be the result of intentional resistance on the part of the learner(s). But even without active resistance, when teachers launch a learning event, they are launching (or better stated, reconstituting) a community of practice, which calls forth a set of norms, practices, discourses, identities (etc.) associated with the particular community. In addition to (or instead of) the intended content of the learning, the learners will inevitably gain facility with their own ways of “doing” this practice: they will learn the rules, how to follow them, how to subvert them, how to use sanctioned aspects of the social language to gain authority in conversation, and much more.

In conclusion, the use of popular culture as a resource in the higher education community can provide a counternarrative to the traditional pedagogical practices usually accepted in academia. We found the common space of popular culture accessible and relatable to all of us, regardless of background or focus. In higher education classrooms, educators often struggle with finding ways to encourage learner agency, authenticity in class work, and a learner-focused curriculum. We contend that the process of examining representations in popular media described in this article helped us accomplish this goal while also informing our understanding of important content that influences our future work as teacher educators.

Through the close examination of our individual popular culture events, we were able to uncover the convergences in our meaning-making, finding ways to assemble the fractured conceptualizations of learning/teaching into a cohesive whole. This pedagogy affords us the opportunity to relearn how we view learning, delving deeper into our beliefs and limitations of the various processes we value in education. We are able to see what is there, not just what we have been taught to see or what we expect to find. Working together to construct our understandings through this process, we step through the popular culture portal into a new area of education. We encourage others in education and related field to engage in similar examinations as a way of developing shared understandings of important concepts in the field, particularly in programs that are interdisciplinary in nature.

Works Cited

Alexander, Patricia A, Diane L. Schallert, and Ralph E. Reynolds. “What is Learning Anyway? A Topographical Perspective Considered.” Educational Psychologist 44.3 (2009): 176-192. Print.

Bruner, Jerome. “A Short History of Psychological Theories of Learning.” Daedalus 133 (2004): 13-20. Print.

Exit Through the Gift Shop. Paranoid Productions, 2010. DVD.

Greeno, James G, Allan M. Collins, and Lauren B. Resnick. Cognition and Learning. Handbook of Educational Psychology 15-46. New York: Simon and Schuster Macmillan, 1996. Print.

Cobb, Paul. “Where is the Mind? Constructivist and Sociocultural Perspectives on Mathematical Development.” Educational Researcher 23.7 (1994): 13-20. Print.

Cunliffe, Leslie. “Gombrich on Art: A Social-Constructivist Interpretation of His Work and Its Relevance to Education.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 32.4 (1998): 61-77. Print.

Davies, Bronwyn, and Rom Harré. “Positioning: The discursive production of selves.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 20.1 (1990): 43-63. Print.

Davis, Dennis S. “Internalization and Participation as Metaphors of Strategic Reading Development.” Theory Into Practice 50.2 (2011): 100-106. Print.

Engestrom, Yrjö. “Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization.” Journal of Education and Work 14.1 (2010): 133-156. Print.

Eun, Barohny. “From Learning to Development: A Sociocultural Approach to Instruction.” Cambridge Journal of Education 40.4 (2010): 401-418. Print.

Gavelek, James R., and Taffy E. Raphael. “Changing Talk About Text: New Roles for Teachers and Students.” Language Arts 73.3 (1996): 182-192. Print.

Gee, James Paul. How to Do Discourse Analysis. New York: Routledge, 2014. Print

—. “Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education.” Review of Research in Education 25 (2000): 99-125. Print.

—. What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Teaching. NewYork: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007. Print.

Gombrich, Ernest. Art and Illusion. 4th ed. London: Phaidon, 1972. Print.

John-Steiner, Vera, and Holbrook Mahn. “Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Development: A Vygotskian Framework.” Educational Psychologist 31.3-4 (1996): 191-206. Print.

Harré, Rom. Personal Being: A Theory for Individual Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1984. Print.

—. “Positioning Theory and Moral Structure of Close Encounters.” Conceptualization of the Person in Social Sciences. Eds. E. Malinvaud and M. A. Glendon. Vatican City: The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, 2005: 296-322. Web. 29 Mar. 2014.

Hickey, Daniel, and Steven Zuiker. “Engaged Participation: A Sociocultural Model of Motivation with Implications for Educational Assessment.” Educational Assessment 10.3 (2005): 277-305. Print.

Hunter, Madeline. Motivation Theory for Teachers. El Segundo, CA: TIP Publications, 1967.

Jengi, Kohan. Orange is the New Black. Prod. Tilted Productions. Netflix, 2014. Web.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Luke, Alan. “Documenting Reproduction and Inequality: Revisiting Jean Anyon’s ‘Social Class and School Knowledge.’” Curriculum Inquiry 40.1 (2010): 167-182. Print.

Matusov, E. “When Solo Activity Is Not Privileged: Participation and Internalization Models of Development.” Human Development 41 (1998): 326-49. Print.

McGrath, Tom, dir. Megamind. Dreamworks Animation, Paramount Pictures, 2010. Film.

Mead, George Herbert. Mind, Self and Society: From the Standpoint of a Mental Behaviorist. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1934. Print.

Moffat, Stephen, and Mark Gatiss. Sherlock. BBC One. Netflix, 2014. Web.

Neely, Anthony. “Girls, Guns, and Zombies: Five Dimensions of Teaching and Learning in The Walking Dead.” Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 2.1 (2015). Web. 4 Nov. 2008

Pennycook, Alastair. Critical Applied Linguistics: A Critical Introduction. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001. Print.

Rogoff, Barbara, Ruth Paradise, Rebeca Mejia Arauz, Maricela Correa-Chavez, and Cathy Angelillo. “Firsthand Learning Through Intent Participation.” Annual Review Psychology 54 (2003): 175-203. Print.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. New York: Scholastic Inc, 1999. Print.

Sawyer, Robert Keith, ed. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. 2.5. New York: Cambridge UP, 2006. Web.

Storey, John. Inventing Popular Culture: From Folklore to Globalization. 1st ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. Print.

Stryker, Sheldon. “The Interplay of Affect and Identity: Exploring the Relationships of Social Structure, Social Interaction, Self, and Emotion.” Identity, Self, and Social Movement. Ed. Sheldon Stryker, Timothy Joseph Owens, and Robert W. White, Minneapolis, MN: University of MN Press, 2000: 21-40. Print.

Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1978. Print.

—. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986. Print.

Wenger, Etienne. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems.” Organization 7.2 (2000): 225-246. Print.

Wertsch, James V. Mind as Action. New York: Oxford UP, 1997. Print.

Wlodkowski, Raymond. Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc, Pub, 2008. Print.

Author Bios:

Kelli Bippert is a third year doctoral fellow at The University of Texas at San Antonio in the Department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching. Her research interests include digital literacy, adolescent struggling readers, and integrating student interests in literacy learning to motivate learners.

Dennis S. Davis is an assistant professor of literacy education at The University of Texas at San Antonio. He received his PhD in Teaching, Learning, and Diversity from Vanderbilt University. He is a former fourth- and fifth-grade teacher whose research focuses on literacy in elementary and middle school contexts. His bio can be found at http://education.utsa.edu/faculty/profile/dennis.davis@utsa.edu.

Margaret Rose Hilburn is a practicing artist and educator. She holds a BFA and MAE from Texas Tech University. Hilburn is currently pursuing a PhD in Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching at The University of Texas at San Antonio. She is currently working as a doctoral fellow, and her research interests include curriculum theory, visual culture, and art education.

Jennifer D. Hooper is a third year doctoral student at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Her research interest focuses on the achievement gap between boys and girls in science courses. Upon graduating with her PhD, she plans to swim with great white sharks and seek employment in higher education.

Deepti Kharod is a doctoral fellow in the Department of Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching at The University of Texas at San Antonio. Her experiences as a journalist, mother, and elementary teacher inform her current work as an educator. Her research focuses on environmental education, preservice teachers, and elementary students.

Cinthia Rodriguez is an elementary math specialist at Northside Independent School District and a doctoral student at The University of Texas at San Antonio. Her research interests include effective teaching practices for diverse populations in the elementary school setting.

Rebecca Stortz is an educator and Ph.D. student at The University of Texas at San Antonio. An avid reader and writer, she strives to incorporate technology and multiliteracies into her classroom experiences. Her research interests include literacy identities, poetry, writing instruction, and teacher education.

Reference Citation:

MLA

Bippert, Kelli, Davis, Dennis, Hilburn, Margaret Rose, Hooper, Jennifer D., Kharod, Deepti, Rodriguez, Cinthia, and Stortz, Rebecca.“(Re)learning about Learning: Using Cases from Popular Media to Extend and Complicate our Understandings of what it Means to Learn and Teach.” Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 3.1 (2016). Web and Print.

APA

Bippert, K., Davis, D., Hilburn, M. R., Hooper, J. D., Kharod, D., Rodriguez, C., and Stortz, R. (2016). (Re)learning about learning: Using cases from popular media to extend and complicate our understandings of what it means to learn and teach. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy. 3(1). http://journaldialogue.org/issues/relearning-about-learning-using-cases-from-popular-media-to-extend-and-complicate-our-understandings-of-what-it-means-to-learn-and-teach/

Academia.edu

Academia.edu