Sheldon S. Kohn

Zayed University

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

sheldon.kohn@zu.ac.ae

Abstract

A shift in focus from supporting or opposing vertical, grand narratives to the horizontal, the ordinary and the everyday, can lead educators to transformative developments. Educators find themselves in a false dichotomy of being restricted to supporting or opposing competing vertical utopian visions of education. Mikhail Epstein’s ideas about transculture can help perplexed educators make a shift from the vertical to the horizontal, focusing their praxis and pedagogy on the ordinary and the everyday, including objects and artifacts of popular culture. In a radical move, Epstein argues that commodification represents resistance to totalitarian controls and impulses; he urges educators to embrace commodification as a strategy for regaining some of what has been lost to corporatist influence in education. When educators shift their focus and perspective from the vertical to the horizontal, they create a space for interference, which involves using difference creatively and can lead to the creation of entirely new culture. Many ideas can be viewed profitably from a transcultural point-of-view, including Alison Cook-Sather’s ideas about metaphor in education and Henry Jenkin’s exploration of the emerging media culture. In the classroom, educators can undertake qualitative experimentation to develop and apply transcultural pedagogy; there is no underlying defined epistemology of education to accompany such work. The current situation in education, and the larger culture, may thus be seen as proto-, i.e., an exciting future that is not predefined and foreclosed. Transculture offers educators a maybe world that allows exploration of the lacunae and lack in every field.

Keywords:

Epstein Mikhail, Transculture, Pedagogy, Commodification, Interference, Proto- Mode, Corporatist Education, Vertical Culture, Horizontal Culture, Creation of Culture

Many educators today are perplexed. They know, or at least think they know, what education ought to be, how exciting and wonderful it is to learn and teach. Many of them do not understand the baffling present moment in education, with its competing claims and counterclaims, its ceaseless calls for reform that are thinly veiled attacks on their professionalism and integrity from people with questionable motives. They also know that today’s certainty may change or disappear before tomorrow. Where education is going and what it will become, the after, remains frustratingly opaque: out of their control and beyond their understanding.2 In this time of constant change and uncertainty, education has become increasingly problematic and confusing for everyone involved in teaching and learning on any level. All too often, educators voices are not heard. Their professional choices seem limited to supporting or opposing someone else’s ideological vision of what education is, and what it should become.

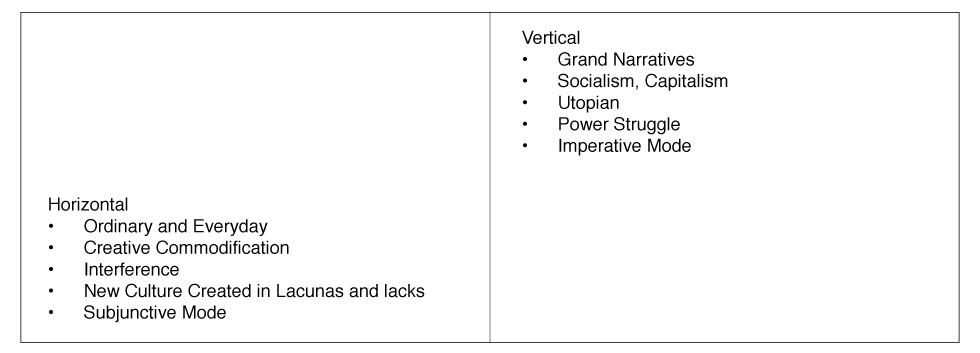

Educators could develop an experimental pedagogy for these new times by shifting their perspectives and efforts from struggling for or against the vertical, grand narratives and strategies designed to transform society, to focusing on the horizontal, the ordinary and everyday, including objects and artifacts of popular culture. Mikhail Epstein’s theory of transculture supports such a shift. The basic structure of transculture is elegant in its simplicity: picture a common x-y axis (see Figure 1).

Figure One: The Vertical and the Horizontal in Culture

The north-south lines on this axis represent vertical forces with the power and the money to force educational change along lines that support their interests and ideology, often in the name of “reform.” The vertical supports and encourages grand ideas and narratives; this is the space where people literally try to force the world to change in accord with their ideological definitions of how things are or should be. Socialism and capitalism, modernism and postmodernism, represent vertical movements of the twentieth-century. There is often, if not always, a utopian strain in vertical ideas, initiatives, and promises. In contrast, the horizontal east-west axis represents the ordinary and the everyday, the realm where most educators live and work. Classroom dynamics occur on the horizontal level, as does the busyness of everyday life. To claim the horizontal as ordinary and everyday is not to deny its power: quite the contrary. Educators who shift their attention and effort from supporting or opposing vertical movements to the ordinary and the everyday of the horizontal can help their students learn how to create new culture. Individual creativity and freedom reside in the horizontal.

Since the early 2000s, moneyed interests and their conservative allies have been pursuing a quest for a vertical transformation of all levels of education by calling for “reform.” As Diane Ravitch explains,

For the past fifteen years, the nation’s public schools have been a prime target for privatization. Unbeknownst to the public, those who would privatize the public schools call themselves “reformers” to disguise their goal. Who could be opposed to “reform”? These days, those who call themselves “education reformers” are likely to be hedge fund managers, entrepreneurs, and billionaires, not educators.

This movement might well be referred to as “corporatism” and its adherents and champions as “corporatists.” For example, after experimenting in the K-12 educational sector, often with very little success, Bill Gates, through his foundation, now “wants nothing less than to overhaul higher education, changing how it is delivered, financed, and regulated” (Parry). In Gates’ utopian educational vision, utilitarian education aligned with corporate goals and ideology will be delivered to students through “a system of education designed for maximum measurability, delivered increasingly through technology” (Parry), a system with many benefits for Microsoft. At a meeting of the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities in 2012, Gates said, “The education we’re currently providing, or the way we’re providing it, just isn’t sustainable” (qtd. in Parry). He insists that educators ask, “How can we use technology as a tool to recreate the entire college experience? How can we provide a better education to more people for less money?” (qtd. in Parry). Such a corporatist view of education now seems so widespread and accepted that in The Chronicle of Higher Education, critics of corporatist goals for education fear to speak because they do not “want to scotch their chances of winning Gates grants” (Parry). The grand vertical vision driving Gates and his allies seems to be creating a system of education in which educators are no longer necessary; the provision of job-related credentials useful to corporatists is to become the sole purpose and function of education. Paul J. LeBlanc, President of Southern New Hampshire University and recipient of funding from the Gates Foundation, explains that education is to be delivered free of educators: “The notion of the faculty member as the deliverer of learning—that’s the piece that we pull out” (qtd. in Parry).

Corporatists powerful or influential enough to support and push vertical agendas for education typically do so without consulting educators or asking for their input, and educators’ reflexive response often becomes adopting instinctive active opposition to any such ideas or programs. Fredric Jameson’s writing, for all its brilliance and influence, illustrates the promises, processes, and perils of embracing a reactively oppositional stance. Jameson offers opposition as the sole legitimate response to market-driven ideology while offering his own vertical prescription for curing our ailing culture and society: “critiques of consumption and commodification can only be truly radical when they specifically include reflection, not merely on the problem of the market itself but, above all, on the nature of socialism as an alternative system” (207). Jameson’s utopian socialism consists of enlightened people joining together in committed opposition to market ideology: in this world, vertical utopian socialist political ideals and projects, which are the only right ones, still offer a vision of a glorious possible future. He goes so far as to claim that “Anti-Utopian thought . . . is flawed” (225). Jameson’s purpose is clearly vertical in its scope and process: “to put an end to metaphysics, and to project the first elements of a vision of some achieved ‘human age,’ in which the ‘hidden hand’ of god, nature, the market, traditional hierarchy, and charismatic leadership will definitely have been disposed of” (336). All that remains is for educators to join others working to implement this utopian vision while waiting patiently, and with apologies to Francis Fukiyama, for the end of history. Jameson always remains convinced that in the battle of utopian visions, socialism will defeat capitalism, and all shall be well. It is profitable, however, to explore what might occur if educators were to embrace and explore a pedagogical approach based in a shift away from grand narratives and vertical domination of culture, from both the right and the left, to the creation of new culture through a focus on the ordinary and the everyday.

As Glenn Altschuler’s study of the history of rock’n’roll illustrates, the creation of culture can have widespread implications for all parts of a society: “Although rock’n’roll was a commodity, produced and distributed by a profit-making industry, and therefore subject to co-optation by the dominant culture, it continued to resist and unsettle ‘mainstream’ values” (34). Rock’n’roll music operated in a space where before there was lack, and it interfered with a wide variety of vertical control strategies and mechanisms of the then-dominant culture: “Rock’n’roll deepened the divide between the generations, helped teenagers differentiate themselves from others, transformed popular culture in the United States, and rattled the reticent by pushing sexuality into the public arena” (34). Those involved in the early days of this creation of new culture had no vertical ambitions whatsoever. They simply wanted to sell as many records as possible. Bill Haley, whose “Rock Around the Clock” became a huge hit, “did not quite know what had hit him” (33). Those in positions of power and control tried to eliminate this new, dangerous commodity while the youth kept listening to, dancing to, and buying it. Rock’n’roll interfered with the dominant hegemonic cultural narrative of the 1950s so the young “could examine and contest the meaning adults ascribed to family, sexuality, and race” (8). Even the term rock’n’roll arose from the position of lack, for there was no name for this new sound: “rock’n’roll was a social construction and not a musical conception. It was, by and large, what DJs and record producers and performers said it was” (23). However much rock’n’roll created new culture from the horizontal, no matter the extent to which social protest, experimentation, and change became linked with rock’n’roll, it remained a commodity. During the 1950s, “record sales nearly tripled, from $213 million in 1954 to $613 million in 1959” (131). The vertical corporate forces in control of popular music at the time opposed rock’n’roll with “a fight against ‘low quality’ music, race music, sexual license, and juvenile delinquency” (134). Industry associations approached Congress to point “to the popularity of rock’n’roll as evidence of a clear and present danger to the American public” (135). No less a diehard reactionary than Barry Goldwater proclaimed that “the airwaves of this country have been flooded with bad music” (qtd. on p. 135). Defenders of rock’n’roll eagerly emphasized its commodity nature and “wrapped themselves in the ideology of free market capitalism, consumer choice, and opposition to censorship” (138). Thus it is that, sometimes, the embrace of commodity choice on the horizontal can rise to the creation of entirely new culture, influencing an entire society and introducing an entirely new world view.

Mikhail Epstein’s ideas about transculture offer a path for educators, and others, to seek freedom even in the face of totalizing vertical demands for intellectual conformity to any ideology. Epstein is a philosopher and cultural theorist who was educated and came of age in the late period of the Soviet Union. Even before the Soviet Union fell, he had begun to look beyond socialism in an effort to imagine what might come next. Educators might follow his lead as they try to imagine what future education might evolve out of the present climate. Given the power, influence, and reach of those promulgating vertical corporatist visions of education, there may seem little left to contest. The future path of education may seem utterly out of educators’ control. There may seem to be no mechanism to halt commodification of who educators are and what they do. However, in what implies a truly radical shift in perspective, Epstein suggests that educators embrace commodification and focus entirely on the agency available in the ordinary and the everyday.

Through his qualitative experimentation, Epstein discovered that a focus on the horizontal, the ordinary and the everyday, can lead educators, and others, to interesting new places, even to the creation of entirely new culture. His experimental work forms the base for what he has developed as the “transcultural movement” (Transcultural 100). Eschewing any temptation to offer an abstract model describing utopian society or to propose grand vertical utopian solutions, Epstein keeps his focus on remaining always “deeply connected with everyday life” (Transcultural 110).

Epstein’s approach to commodification exemplifies how transcultural thinking challenges, engages, and subverts much of what Western cultural studies teaches about the relations of power and culture. He finds freedom in the horizontal, not in the vertical, though much energy is expended to make us believe otherwise. While educators may feel powerless in the face of the corporatist movement in education, on the horizontal level, transculture offers a stance to promote individual freedom through even such simple acts as choice in commodity culture.

Development and application of a pedagogy rooted in transculture would replace any focus on grand narratives or overarching vertical strategies developed to guide and mold an entire society along ideological grounds to the horizontal vision guiding an individual who must develop agency in things as they are. The utopian strain in transculture is individual, not collective: “the resurrection of utopia after the death of utopia, no longer as a social project with claims of transforming the world, but as a new intensity of intellectual vision and a broader horizon for the individual” (Transcultural 100). While living and working in a totalitarian society, Epstein searched for methodology to move his focus in cultural theory from the vertical, which was carefully guarded by the vast apparatus of the Soviet state, to the horizontal, which everywhere and always accommodates individual variation. The impetus for his development of transculture was “to activate the transsocial potentials inherent in human individuals rather than those oppositional or revolutionary elements pertaining to specific social groups” (Transcultural 102). Educators may easily find sympathy with the idea of eschewing reactive resistance to the empowered collective, in their case corporatism and market ideology in education, in favor of individual agency, discovery, and freedom for both themselves and their students.

In a certain sense, after embracing the shift from the vertical to the horizontal, educators would continue as if nothing had changed. However, everything would have changed, for transculture opens the path to create culture, even when educators are commodified. The shift from supporting or opposing competing vertical movements to seeking agency in the horizontal represents a fundamental shift in stance that allows for individual variation and unpredictability in education. At the time Epstein first began to look for what might follow the Soviet state, one could have concluded that such efforts were futile; now they can be seen as prescient. Educators making the same shift from the vertical to the horizontal enter what has shown itself to be a fertile area for qualitative experimentation. This change in stance, this shift in attitude, is not intended to challenge directly corporatist control of educators’ professional lives and work, but it forms a critical part of the process of seeking the “after” that seems elusive in the current educational milieu.

In the realm of vertical utopianism, individual choice remains limited only to embracing or opposing commodification, which is separated from culture. Epstein insists that commodification is not foreign to culture: “commodification seems to be built into the very enterprise of culture as one of its (self-) transcending dimensions” (Transcultural 107). From a transcultural view, any insistence that educators must reactively oppose or thoughtlessly embrace commodification rests on a vertical foundation as shaky as corporatists’ insistence that totalizing market control must now define education. Culture without commodification, such as that practiced in the late Soviet Union, speaks to no one:

Culture stopped being what people want to read, view, and listen to, and for which they are ready to pay. It became what people are obliged to read, view, and listen to in order to think and feel in the way that the state wants them to. The Soviet system struggled with the exteriorization of the internal life, the process that at a certain point generates art as commodity. What the Soviet system required was, on the contrary, the interiorization of social life, of the officially approved artistic works, mythological schemes, philosophical concepts, and political imperatives that the state imposed on people. (Transcultural 108, italics added)

Western educators may become uncomfortable with the implications of Epstein’s further claim that commodification “can be regarded as a grass-roots challenge to all kinds of totalitarian uses and abuses of culture” (Transcultural 108). Totalitarian ideologies, including corporatism, seek to control how questions can be framed and do not accept individual responses as cogent analyses. Without a shift to the horizontal, personal responses to vertical claims and strictures may become definitional for individuals, leaving little room for alternate approaches or new choices within predefined utopian totalities. Transculture offers the shift in individual perspective and effort towards the horizontal, the ordinary and the everyday, as transformative and resistant to all totalitarian impulses and programs. Though it seems the polar opposite of what many Westerners have been taught and come to believe, creative commodification allows educators to regain some of what has been lost. Commodification as resistance offers a welcome tactic to perplexed educators after they understand the necessary shift from the vertical to the horizontal.

Anyone schooled in Western cultural studies may well be shocked when first encountering Epstein’s claim that the “status of the commodity secures freedom in the relationship between those who produce and those who consume” (Transcultural 109). Although such a claim seems to embrace totalizing market ideology, which many educators would be loathe to do, Soviet socialist culture taught Epstein that when “culture is decommodified it becomes subject to exploitation by the power that is indifferent to what people want to receive and are able to produce” (Transcultural 109). The decommodified culture Epstein knew consisted of “ungifted producers offer[ing] unwanted products to uninterested consumers” (Transcultural 108).

Few educators would embrace decommodified culture in practice. Although educators on all levels may cringe, for good reason, when they consider the baleful impacts consumer commodity culture has made on their students’ intellectual and emotional growth and development, they cannot claim that commodity products are unwanted or that consumers are uninterested. Much effort goes into making people care whether, for example, they prefer Coke or Pepsi. American commodity culture may be regrettable in almost every way, but bad taste can be an expression of freedom.3 Commodification, in addition to its numerous flaws, shortcomings, and betrayals, offers choice, including the individual’s choice to choose something better, which is a nice spot for educators and students to explore. Individual choice in commodity culture, when multiplied over many individuals, can make a large impact on what gets offered. Educators’ agency, no matter the impositions and strictures of vertical culture, presupposes their ability to guide students as they make the choices necessary to navigate through commodity culture. To put it another way, although educators focused on the ordinary and the everyday may not change the World, they may well change many worlds.

Consumer commodities offer the worst of culture, simultaneously wasteful and frivolous; they seem to provide an illusion of meaningful choice. Yet, these same products once “served as signs of liberation for the Soviet people, and also as signs of culture because culture is everything that is beyond permission, that transcends the boundaries of the allowable” (Transcultural 109). Toothpaste and deodorant may seem a poor substitute for revolutionary protest against corporatist thinking, yet, as Epstein writes, “challenge to the structures of power is what the greatest creations of art share with the most trivial products of commodity culture” (Transcultural 110).

Epstein knows well “the bitterness which those of us working in the humanities feel when witnessing the lack of demand for our expertise, our vocation, and when we observe an arrogant contempt towards that which we consider the focus of our life” (Transformative 1). Educators join many who hold serious and legitimate concerns about sustainability and equity in what seems a static society creative only in pursuit of profit and puerile in pursuit of everything else. While Epstein rejoices in the freedom that lies in commodities, educators long for freedom from commodification. Educators have learned to live and work in the shadow of overwhelming vertical demands for conformity; their first impulse may be reactive opposition to Epstein’s views, along the lines that Jameson would encourage. However, the transcultural practice of interference offers a way for those holding radically divergent views to influence each other in the lack and lacunae beyond difference. Vertical movements isolate and exacerbate difference, forcing educators to choose one of only two views. They offer “no space for difference as a category that is itself different from both identity and opposition” (Transcultural 92). Transculture locates difference at the point where contrasting, even conflicting, views begin to operate on each other, not as the end of engagement. Vertical ideology “renders people only schematic illustrations of some abstract principles: ‘good and bad,’ ‘rich and poor,’ ‘oppressors and revolutionaries,’” allowing only two positions: “opposition and unity” (Transcultural 95). In contrast, interference creates productive difference through non-dialectical discourse: “‘Interference’ is not taken here to mean an intrusion or intervention, but, in line with its definition in physics, [interference] denotes the mutual action of two or more waves of sound or light. Such an effect is found, for instance, in the butterfly’s colorful markings” (Transformative 60). From a transcultural view, rather than creating dualities leading to false, forced choices, differences “strengthen our need for each other” (Transcultural 99). Though contrasting views inevitably differ in vital, fundamental ways, interference places each as open to interaction with the other so that something new can be created: “Transculture is an experience of dwelling in the neutral spaces and lacunas between cultural demarcations. Transculture is not simply a mode of integrating cultural differences but a mode of creating something different from difference itself” (Transcultural 112).

Stanley Fish reported an experience that could be viewed in terms of interference. Distressed by the inability of graduate students, who are also instructors of English composition, to write literate sentences, Fish “came to the conclusion that unless writing courses focus exclusively on writing they are a sham.” Fish reports being “slightly uncomfortable” at finding support for his conclusion in a white paper from the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, an organization “[f]ounded by Lynne Cheney and Jerry Martin in 1995.” While he finds agreement with the organization’s insistence that composition courses focus exclusively on developing students’ writing skills, he also recognizes that Cheney and Martin have a political goal of “reconfiguring the academy according to conservative ideas and agendas” which he does not support. In accord with the transcultural practice of interference, Fish explores the space between the lacunas where lack exists. Even if reluctantly, he is influenced in his effort to influence, and he creates something different from difference.

For interference to become an essential process for educators, they need to develop some new habits and eschew as mere distraction any practice of reacting reflexively in opposition to vertical forces, such as corporatism in education. It is not an overstatement to place the transcultural shift from the vertical to the horizontal as “the next step in the ongoing human quest for freedom, in this case the liberation from the prison-house of language and a variety of artificial, self-imposed, and self-deifying cultural identities” (Epstein, Transformative 60).

If Epstein’s ideas about transculture describe existing educational culture, one expects to find ideas from other scholars that may be viewed productively from the transcultural perspective. Alison Cook-Sather, for example, objects to “orthodox pedagogies—scripted approaches to teaching and learning—that teachers in public schools are pressured to embrace” (“Change” 345). Her ideas support empowering teachers and students to “learn to resist the imposition of oppressive, disempowering, and commonly accepted educational practices” (“Change” 346). Through a pedagogy that incorporates a focus on the ordinary and the everyday, Cook-Sather hopes to provoke “an interaction with metaphors presented by popular culture and a choice to take them on in an active and critical way” (“Movements” 947). In line with the transcultural idea of creative commodification, Cook-Sather notes, “We can deliberately choose other ways of thinking, naming, and being, even as the dominant models of schooling and many of the people who function within them are trying to keep us contained and controlled” (“Movements” 948-949). She identifies the two dominant metaphors of education (production and cure) as vertical control mechanisms, though she does not use the terminology of transculture: “Because metaphors not only foreground certain qualities but also obscure and eliminate others, they can lead people to assume or accept that one particular way of thinking is the only way to think and one set of particular practices the only possible set” (“Movements” 950). Further, Cook-Sather proposes that education “must be guided by metaphors that unsettle, that expect students to seek, find, and invent what we do not know, that lead us not only to imagine but also to create other possible worlds” (“Movements” 959), a goal much in tune with Epstein’s ideas about transculture. The particular metaphor Cook-Sather prefers is “translation”: “It casts students as active agents engaged in an ongoing, interactive, and reflective process of making new versions of themselves—versions that are at once duplications, revisions, and recreations, with meaning lost, preserved, and created anew with different textures, boundaries, and resonances” (“Movements” 961). Metaphors, not methods, drive the possibilities arising in Cook-Sather’s twenty-first century pedagogy: “When the school becomes a space within which students can actively compose and re-constitute themselves, the school can become a revolutionary site that can open up more diverse ways for students to understand and participate in the world” (“Movements” 962).

Cook-Sather’s translation framework, like that of transculture, focuses on educational process over product: “These processes are never finished; they are always open to further revision and always lead to further re-renderings” (“Translation” 219). The obsession with data and measurement in education has created a situation of “fixed ness [sic] in the production and finishedness as an outcome of that education: educational contexts are structured toward achieving finishedness, and success is evaluated in terms of finishedness” (“Translation” 230). She argues that the “generative work of meaning making unfolds in the spaces between people and ideas,” which Epstein identifies as the lack or lacuna where interference is possible (Education 25). When a metaphor becomes imposed as a controlling vision, rather than a symbolic statement of possibility, the linking verb transforms to the imperative mode, and the subjunctive mode of suggestion disappears in favor of command and control. Metaphors conceptualizing vertical definitions of educational possibility become totalitarian threats resisted through an educator’s embrace of creative commodification in the horizontal.

In media studies, Henry Jenkins revels in the nature of emerging culture, which he sees as developing unpredictably. He finds a strong disconnect between the conception of literacy operating in formal education and what students want and need to know, understand, and be able to do. Average teenagers worldwide, so long as they are on the privileged side of the digital divide, routinely far exceed any existing curricular standards for media literacy: “A teenager doing homework may juggle four or five windows, scan the Web, listen to and download MP3 files, chat with friends, word-process a paper, and respond to e-mail, shifting rapidly among tasks” (17). Emerging artistic and literary forms and media cannot be categorized and contained through existing academic rules and boundaries. The Matrix film series offers an exemplar of “transmedia storytelling”: “A transmedia story unfolds across multiple media platforms, with each new text making a distinctive and valuable contribution to the whole” (95-96). Such storytelling interferes with the archetype, beloved of many educators, of the solitary creative genius isolated from everyone else: “storytellers are developing a more collaborative model of authorship, co-creating content with artists with different visions and experiences” (96). Narratives developed collaboratively lead to new places not confined to traditional forms or media. They cannot be examined within traditional academic boundaries: “storytelling has become the art of world building, as artists create compelling environments that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work or even a single medium” (114). Epstein would add that we cannot begin to imagine where such developments of narrative will lead: “In terms of literature, we live in the epoch of Beowulf and medieval epic songs. An abysmal gap separates us from the future Tolstoys and Joyces, whom we are unable even to predict” (Transformative 33).

In emerging culture, the collaborative, yet commodified, nature of the Internet challenges assumptions and rules about what constitutes good and useful criticism. Vertical strictures and controls limit educators to rules of criticism based on forms, patterns, and assumptions that no longer apply: “Criticism may once have been a meeting of two minds—the critic and the author—but now there are multiple authors and multiple critics” (Jenkins 128). Students who operate in collaborative intellectual communities and create works with many hands and eyes seem unwelcome in many educational institutions: “Our schools are not teaching what it means to live and work in . . . knowledge communities, but popular culture may be doing so” (129). Play, and not schooling, popular culture, and not education, now provide students with entry points into exciting new worlds full of possibility.

The constricting, restricting nature of teaching and learning in our corporatized era limits both students’ and educators’ possibilities: “educators are coming to value the learning that occurs in . . . informal and recreational spaces, especially as they confront the constraints imposed on learning via educational policies that seemingly value only what can be counted on a standardized test” (Jenkins 177). Students may well be learning what they really need to know outside of schooling through activities such as participating in online communities: “literacy experts are recognizing that enacting, reciting, and appropriating elements from preexisting stories is a valuable and organic part of the process by which children develop cultural literacy” (Jenkins 177).

An educator interested in exploring the pedagogical implications arising from transculture can pursue qualitative experimentation: “an experiment in culture has no reference point for verification, no means of being tested objectively in relation to external reality. It neither confirms nor rejects any preliminary postulate but aims to multiply and disseminate new forms of expression or new paradigms of knowledge” (Epstein, Transcultural 6). An experiment in transculture “problematize[s] a particular cultural symbol or system, to potentiate a series of alternative symbols rather than to solve a problem or to actualize a specific potential” (Epstein, Transcultural 7). Such goals are fully in accord with the deepest nature of education as “one of the most mysterious and intimate moments in life” (Epstein, Transformative 291).

Adam Lefstein’s 2005 analysis of deep divisions in Western culture could be read as transcultural experimentation; fully in the horizontal mode of interference, he advises readers to “judge the extent to which the competing visions resonate with their own thinking about the issues” (335). In a statement that could have been written explicitly from a transcultural point-of-view, Lefstein argues that teaching materials and curriculum guides should by design create space for interference:

[Their] message could be reinforced by casting the ideas in a less confident and authoritative tone, for example, transforming the imperative ‘pose the following question’ to the subjunctive ‘one possibility is to explore with the pupils the following question’. This stylistic shift would imply that instead of representing rules with which teachers must comply, the guidance is a collection of resources and ideas from which teachers may draw. (349-350)

Movement from the vertical imperative to the horizontal subjunctive mode empowers educators to make the same shift with their students. Although perhaps subtle, a permissive stance, instead of a commanding tone, could make all the difference in what students are taught about what education really means. Transculture concedes grand narratives and overarching utopian claims and theories to the vertical in favor of horizontal transcendence grounded in the ordinary and everyday work of educators in their classrooms.

The horizontal shift Epstein proposes becomes clearer when one considers what might follow transcultural experimentation in a classroom. An educator’s move towards applying transculture, or searching for an experimental pedagogy, could begin with a focus on self and a commitment to becoming experimental in intention and design, in a shift from the vertical imperative mode (“Do this!”) to the horizontal subjunctive mode (“Consider this as one choice.”). Movement towards horizontal transcendence evolves unexpectedly and unpredictably, creating culture, not spinning utopian educational narratives. Rather than imperatively insisting that educators accept uncritically yet one more epistemology of teaching, transculture subjunctively invites them to experiment. Transcultural experimentation “develops a subjunctive modality . . . , attempting to broaden the range of possibilities and to transfer the status of experimentation from certainty to uncertainty, from ‘result’ to ‘draft’” (Epstein, Transcultural 7). Educators are invited to move from the isolation, obedience, and allegiance corporatist education demands toward interference, where “differences no longer isolate . . . but rather open . . . perspectives of both self-differentiation and mutual involvement” (Epstein, Transcultural 9).

Educators who base their work in opposition to corporatist vertical strictures, as Jameson insists they must, remain stuck in a countercultural echo chamber more than forty years old; it is a deterministic world that neither surprises nor delights. The stance these educators take concedes the battle before the fight even begins because there is nothing productive or dynamic in such an approach. Transculture’s focus on horizontal transcendence “by acceptance and understanding” teaches the teacher how “to embrace and encircle” rather than how “to define, analyze, and oppose” (Epstein, Transcultural 45). Transculture moves educators towards a necessary rethinking of academic subjects and a deliberate move away from enforced and artificial curricular boundaries that, for example, claim to assess students’ writing skills through standardized testing requiring no writing. Transculture’s experimental curriculum’s “subject matter . . . [is] ‘everything’ and its methodological criteria ‘all’” (Epstein, Transcultural 46). Transculture allows for creation of new culture, embracing all that could imply for educators’ pedagogy and students’ creativity.

In transcultural experimentation, educators forsake the approach to culture they have applied, as well as methods and practices they have used for many seasons. The shift to transculture reveals and uncovers “culture after culture as there is life after life in other transcendent dimensions” (Epstein, Transcultural 65). Many educators working in today’s corporatist-collectivist, data-driven authoritarian educational market culture will find themselves much in sympathy with Epstein’s intention to interfere, never to blend.

Transculture offers educators “a radical transition from finality to initiation as a mode of thinking” (Epstein, After 332). Nowhere does this become clearer than in Epstein’s conception of the “proto-.” As the idea of “post” (as in postmodernism) dominated the intellectual culture in the latter part of the twentieth century, Epstein argues that the “present era . . . needs to be redefined, probably in terms of ‘proto-’ rather than ‘post-’” (After 280). Proto- manifests itself in uncertainty and lack of specificity: “A beginning . . . understood as leading to an open future and manifesting possibilities for continuation and an impossibility of ending can be designated as ‘proto’” (Epstein, After 331). Proto- cannot be defined or otherwise restricted: “Proto-, as it is emerging on the boundary of post-, is not proto-something, it is proto in itself” (Epstein, After 334). It expresses the transcultural mindset:

Proto- signals a humble awareness of the fact that we live in the earliest stage of an unknown civilization; that we have tapped into some secret source of power and knowledge that can eventually destroy us; that all of our glorious achievements to this point are only pale prototypes of what the coming bio- and info- technologies promise to bring. (Epstein, Transformative 32)

For educators restricted and bound by competing vertical utopian claims and counterclaims, “proto” offers “a state of promise, . . . expectation without determination” (Epstein, After 335). Educators can again approach the future in a state of excitement, in spite of all vertical attempts to define and control it or them in the form of standards, curriculum, testing, bureaucracy, control, and surveillance. As the living, breathing, undefined future, students now are efficiently ignored, predefined, sorted, and foreclosed. If educators do not want, for themselves or their students, what Epstein refers to as the “dead, objectified future . . . that we now find ourselves living” (After 335), they might begin creating new culture by attending to the ordinary and the everyday, privileging the horizontal not the vertical.

Although education is often the focus, one is tempted to say “the victim,” of massive vertical forces—true education ever resists control and standardization. Education is a process well suited to the horizontal focus Epstein urges: “Education is an improvisational activity that exercises the human capacity for wonder and unpredictability. Education is not just talking about what we already know; it initiates a social event of creative co-thinking, where what is unknown is revealed to us only in the presence of others” (Epstein, Transformative 292). Through a dynamic that Faulkner would appreciate, the past once again becomes part of every person’s present and his or her future: “The postmodern addiction to citations and intertextuality brought the past to the brink of extinction through the expanding dialogue with the present. The electronic web in particular brings the past preserved in texts to the fingertips of our contemporaries who cut, copy, and paste the past according to their own projects and constructive needs” (Epstein, Transcultural 153).

Student writing offers a promising area for transcultural experimentation. In their schooling, students often learn that academic writing is a solitary, isolating, task-driven activity that rarely requires creativity, and, seldom, if ever, results in joy. Epstein invites educators to consider what might happen were students free to write on the utterly commonplace, for example, on garbage, fences, or a favorite song or movie from their popular culture. Likewise, we might ponder what would happen were a group of educators to come together and write collectively on a topic they all chose, for example, “teacher and disciple” or “Myth and tolerance,” maybe “Money” (Epstein, Transcultural 41). At the very least, both educators and students might find that they have something interesting to say, after all.

Schooling as presently constituted routinely fails to meet the needs of creative and passionate students: “someone who has just published her first online novel finds it disappointing to return to the classroom where her work is going to be read only by the teacher and feedback may be very limited” (Jenkins 184). Such students find themselves in the paradoxical position of having to “wait for the school bell to ring so they can focus on their writing” (Jenkins 184). Educators may well object that such writing is undisciplined apprentice work that lacks rigor and is of low quality. Even were this absolutely the case, students who cannot wait to go home and write “are passionate about writing because they are passionate about what they are writing about” (Jenkins 185), which is not how many students feel about and approach typical academic writing assignments. Transcultural pedagogy could bring the fervor of haphazard creativity back into the classroom. Leveraging the skills in collaboration and technology students have already mastered, educators may begin to expect, and receive, interesting, perhaps even amazing, writing on topics never explored before in schooling because they were never before admitted to an academic context.

Transculture remains passionately nondeterministic; there can be no one model for transcultural pedagogy. It is subjunctive and horizontal in both conception and practice:

Practice creates something new altogether that was not contained in the object previously explored or explained by theory. . . . Thus practice, even when it is based on a particular theory, cannot simply be reduced to that theory. It creates a possibility for new theories that in turn create possibilities for new practices. (Epstein, Transformative 58)

Educators will develop unique transcultural pedagogies and practices based on the results of their individual qualitative experiments, and all results remain drafts, starting points for further experimentation. Transcultural pedagogy invites educators to focus on the ordinary and the everyday, to transform what often seems to students, and to their teachers, a series of lifeless and pointless tasks and assessments into an exciting craft. Students may begin acting creatively in ways that their educators never imagined possible. In contrast to the certainties of corporatist education, transculture offers a maybe world; it is a first draft of a culture we cannot yet imagine. No matter what the vertical pressures and demands of the moment, educators remain the people, perhaps the only people, who can show their students how commodification can serve the cause of freedom, though it seems that does not; what it means to live in the proto-, as we do; and where to seek the lack and lacuna to set forth on explorations that lead to the creation of new culture.

Endnotes

[1] I would like to thank my colleague Ximena Cordova for her very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

[2] It is interesting to note titles of some recent books in this regard: Terry Eagleton wrote After Theory Valentine Cunningham wrote Reading after Theory; and Mikhail Epstein wrote After the Future. After seems to be an important contemporary intellectual trope.

[3] John Waters, for example, created an aesthetic based on bad taste. His autobiography is Shock Value: A Tasteful Book About Bad Taste. One wonders if a decommodified culture could hold space for his work.

Works Cited

Altschuler, Glenn C. All Shook Up: How Rock’n’Roll Changed America. Oxford UP, 2003.

Cook-Sather, Alison. “Change Based on What the Students Say: Preparing Teachers for a Paradoxical Model of Leadership.” International Journal of Leadership in Education, vol. 9, no. 4, 2006, pp. 345-358.

—. Education is Translation: A Metaphor for Change in Learning and Teaching. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

—. “Movements of Mind: The Matrix, Metaphors, and Re-Imagining Education.” Teachers College Record, vol. 105, no. 6, 2003, pp. 946-977.

—. “Translation: An Alternative Framework for Conceptualizing and Supporting School Reform Efforts.” Educational Theory, vol. 59, no. 2, 2009, pp. 217-231.

Cunningham, Valentine. Reading after Theory. Blackwell, 2002.

Eagleton, Terry. After Theory. Basic Books, 2003.

Epstein, Mikhail. After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture. University of Massachusetts Press, 1995.

—. and Ellen Berry. Transcultural Experiments: Russian and American Models of Creative Communication. St. Martin’s, 1999.

—. Transformative Humanities: A Manifesto. Bloomsbury, 2012.

Fish, Stanley. “What Should Colleges Teach?” Think Again Blog. The New York Times Company, 24 August 2009, opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/24/what-should-colleges-teach/?_r=0 Accessed 18 November 2016.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press, 2006.

Lefstein, Adam. “Thinking about the Technical and the Personal in Teaching.” Cambridge Journal of Education, vol. 35, no. 3, 2005, pp. 333-356.

Parry, Marc, Kelly Field, and Beckie Supiano. “The Gates Effect.” Chronicle of Higher Education, 13 July 2013, www.chronicle.com/article/The-Gates-Effect/140323/. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Ravitch, Diane. “When Public Goes Private, as Trump Wants: What Happens?” New York Review of Books, 8 December 2016, www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/12/08/when-public-goes-private-as-trump-wants-what-happens/. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Waters, John. Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste. New York: Avalon, 1981.

Author Bio

While working as an English Teacher in secondary education from 2001-2009, Sheldon Kohn began to explore ways to negotiate freedom as an educator while being subject to commodification, marketplace ideology, and the tyranny of standardized tests. The philosophy of Mikhail Epstein spoke to him from the first time he read it, and he immediately saw its applicability to education. Since 2010, he has lived and worked in Abu Dhabi, UAE, where he serves as Chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies at Zayed University. His department includes professors and instructors in science, information technology, and social science who teach courses in the General Education curriculum. His current projects include an exploration of how a culturally sensitive focus on the ordinary and the everyday could help L2 college students improve their written work in English. He is an active member of PCA/ACA and has a page available on academia.edu.

Reference Citation

MLA

Karshner, Edward. “The Diyinii of Naachid: Diné Rhetoric as Ritual.” Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy, vol. 3, no. 2, 2016, http://journaldialogue.org/issues/the-diyinii-of-naachid-dine1-rhetoric-as-ritual/.

APA

Kohn, S. (2016). From the vertical to the horizontal: Introducing Mikhail Epstein’s transculture to perplexed educators. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy. 3(2). http://journaldialogue.org/issues/from-the-vertical-to-the-horizontal-introducing-mikhail-epsteins-transculture-to-perplexed-educators/

Academia.edu

Academia.edu