Gene McQuillan

Kingsborough Community College /The City University of New York

Brooklyn, NY, USA

genekcc@aol.com

Abstract

Teachers often feature graphic novels in college courses, and recent research notes how these texts can help make the process of reading more engaging as well as more complex. Graphic novels help enhance a variety of “literacies;” they offer bold representations of people dealing with trauma or marginalization; they explore how “texts” can be re-invented; they exemplify how verbal and visual texts are often adapted; they are ideal primers for introducing basic concepts of “post-modernism.” However, two recurring textual complications in graphic novels can pose difficulties for students who are writing about ethical questions. First, graphic novels often present crucial scenes by relying heavily on the use of verbal silence (or near silence) while emphasizing visual images; second, the deeper ethical dimensions of such scenes are suggested rather than discussed through narration or dialogue. This article will explain some of the challenges and options for writing about graphic novels and ethics.

Keywords: Graphic novels, ethics, literacies, Art Spiegelman, Maus, Alison Bechdel, Fun Home

I am committed to using graphic novels in my English courses. This commitment can be a heavy one–in my case, it sometimes weighs about 40 pounds. If one stopped by my Introduction to Literature course at Kingsborough Community College (the City University of New York), one could see exactly what I mean.

A substantial part of the course focuses on Art Spiegelman’s Maus (and Meta-Maus); these texts are often paired with excerpts from Elie Wiesel’s Night and recent critical commentaries about constructing the “canon.” During one class in the Maus sequence, I bring two large bags of books, all of them graphic novels.1 I leave class with a lighter load, since ALL of the students browse through the texts and choose one as an independent reading. Certain texts get snatched quickly: Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, Kejii Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, Marisa Acocella Marchetto’s Cancer Vixen, Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World, Adrian Tomine’s Shortcomings, Frank Miller’s Sin City and Brian Vaughn’s V: The Last Man. Other texts usually require a bit more “selling”: Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Joe Sacco’s Palestine, Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s Skim, Mat Johnson’s Incognegro, Gene Luen Yang’s American-Born Chinese, Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, Emmanuel Guibert’s The Photographer and, of course, Will Eisner’s classic, A Contract with God.

Reasons for Featuring Graphic Novels in a Course

Graphic novels tend to create converts, and converts often get a bit carried away. This sort of enthusiasm is often evident when students browse through graphic novels. The students can and often do take more than one text, and they soon realize that there is a wide and surprising world of “literary” texts out there. While I surely appreciate their engagement, I have also been investigating whether and how graphic novels will remain an essential component of my teaching practices. Why bring bags of graphic novels to a college Introduction to Literature course? At least five criteria seem crucial. Graphic novels:

- Help students of many different readings levels and backgrounds develop a wide range of “literacies.” This process relies on a very broad and nuanced approach to how people and groups “read” and construct meaning.2

- Encourage innovative texts for encouraging dialogues about “otherness,” about illness, about marginalized groups and outsiders, about the ways in which both individuals and groups use images and narratives to create, assign and/or challenge identities.3

- Provide concrete examples of how texts are “constructed” or “re-invented,” since even simple matters such as fonts and punctuation and pages are often radically re-imagined.4

- Represent an on-going shift toward “visual culture,” and allow students to get a clearer sense of how verbal and visual texts are adapted for different media and how they have they own distinct discursive expectations.5

- Serve as ideal primers for introducing students to some basic concepts and binary tensions of “post-modernism”: construction and deconstruction, chance and design, irony and intertextuality, high art and pop culture, linear and non-linear texts.6

My research about graphic novels also led to an innocuous blog entitled “Getting Graphic.” The blog is primarily a basic review of recent scholarship on teaching such texts, yet one of its concluding claims led to writing this article: “Graphic novels have received attention for their ability to motivate reluctant readers and support multiliteracies. However, graphic novels are not only for readers who struggle. Sequential art benefits already motivated students and supports the examination of ethical issues with gifted students” (4; italics added). I am convinced that graphic novels can present some serious challenges for all students, for “reluctant readers” as well as “already motivated students” and “gifted students.” Yet I will be direct about my concern: a series of problems can arise when writing assignments about graphic novels encourage students to engage in an “examination of ethical issues.”

Of course, the previous sentence demands some immediate clarifications. As for “writing assignments,” I will focus on writing courses in community colleges, especially those courses known as WAC and/or WI sections: the acronyms stand for Writing-Across-the-Curriculum and/or Writing Intensive. I have been tutoring and teaching at CUNY (the City University of New York) since 1983, and I have been a full-time English professor at KCC (Kingsborough Community College) in Brooklyn since 1993. While at KCC I’ve often taught ENG 30, an “Introduction to Literature” course, also listed as a Writing Intensive / Honors course. In practical terms, we do numerous revised and in-class essays, and roughly 30 percent of the students will be affiliated with the college’s Honors Program. I have often taught texts such as Maus, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, David Small’s Stitches, and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home in ENG 30, and while doing so, I have had to remain aware of a basic fact. I am teaching a Writing Intensive course about Literature in which very, very few students—even those in the Honors program—are potential English majors. As I write this, no program for an English major or minor is available at KCC, so for the great majority of students, “Introduction to Literature” is their first and last English elective. Roughly 60 percent of our incoming students speak English as their second language, many represent the first generation in their family to attend college, and many have a family income below $30,000 a year. The challenge of teaching such courses has become a serious issue at many other colleges, and an intriguing study of such courses appears in a 2015 article from The CEA [College English Association] Forum. The article “‘You are asking me to do more than just read a book’: Student Reading in a General Literature Course” makes a series of claims about how a literature course for non-majors can and should work. The authors state:

Study findings indicate that both students and teachers find students to be most engaged in literature when given some autonomy to direct their reading choices and when prompted to identify the relevance of texts to their lived experiences; that a literature course for non-majors offers opportunities for students to develop or reclaim reading habits; and that both students and teachers perceive such a course to offer students opportunities to learn transferable reading and writing skills. (Amicucci et al. 2-3)

This statement serves to identify a few crucial ways in which teachers and students alike can make active decisions about finding readings that are both serious and appealing. As I consider the article’s references “autonomy” or “relevance” or “reclaiming” certain “transferable” skills, they seem both familiar and convincing; they neatly summarize much of what I aim to do in my daily practice as a teacher.

Graphic novels would thus appear to be a helpful resource in a course for non-majors. Yet the term “graphic novel” also deserves clarification, since “graphic novels” are so varied that generalizing about them would be pointless. Thus, my argument will focus on four well-known graphic memoirs: I will directly discuss Spiegelman’s Maus and Bechdel’s Fun Home, and I will briefly note the relevance of Satrapi’s Persepolis and Small’s Stitches. All are memoirs in which an adult tries to reconstruct how the traumas of his or her youth are paired with very painful or contentious family matters. While teaching these texts, I’ve seen ample evidence in support of the five criteria previously noted: improving literacies, discussing otherness, deconstructing texts, analyzing visual culture, and contextualizing post-modernism. Reluctant and struggling readers have eagerly asked for my personal copies of Persepolis II and Maus II, even though these sequels are not assigned. Other students have shared their interests in comics and other forms of visual culture, such as anime and manga, providing us with accessible examples of how terms such as “literature” and “literacy” are far from self-explanatory.

Students from highly diverse (and potentially divisive) backgrounds have worked together to explain, for example, how and why religious “veils” are significant or how societies have created complex (and often vicious) associations between people and animals. Noting how these associations are often visualized has lead in turn to discussions of how seemingly neutral and objective images, such as a newspaper photograph, draw from a deep well of assumptions. Such discussions became concrete when we considered two seemingly simple concepts, namely “page” and “scene.” We read Meta-Maus and noted how Spiegelman often drew many different versions of the same page, or we chose a single scene from a text and watched as it is then adapted, as one can see in the film version of Persepolis; after this, students needed little convincing that artists and authors actively “construct” their texts. We have had vigorous discussions of what qualifies as a “literary/non-literary” or “fiction/non-fiction” texts. Can a “comic” (or a Campbell soup can or an upturned toilet bowl) be considered “art?” Can they explain why the best-seller list of the New York Times initially listed Maus as “fiction?” Also, students were often highly motivated when other students spoke boldly of how their experiences inform their reading. Examples abound in the highly diverse microcosm of KCC classrooms, and when students speak of the Holocaust survivor in their family or the reasons why they wear hijab or a decision to “come out” to their family, one can almost feel the room spin as the students’ attention and voices shift to become more attuned to a new revelation.

KCC teachers continually try to navigate the various and shifting cultural codes in a college where a “typical” class of twenty-five students might feature a dozen nationalities/ethnicities, an even higher number of bilingual students, and a fascinating range of religious beliefs. It would require a far longer text than this to try to register even a partial set of these cultural variables and to suggest some methods for addressing them in a class setting. My goals are more modest, and will focus on certain distinct formal aspects of graphic novels that may become a crucial part of the process of writing a complex “examination of ethical issues.” Graphic novels surely share numerous formal characteristics with traditional prose narratives; for example, both a graphic novel and a traditional novel might feature multiple narrative lines as well as distinct narrative voices and perspectives. These multiple viewpoints might in turn encourage readers to consider a more nuanced and multi-faceted discussion of ethical issues. However, there are certain features of graphic novels—such as presenting crucial scenes by relying heavily on visual images while offering little or no verbal contexts—which might engage students as readers while also presenting them with a potentially frustrating occasion for doing academic writing.

What Do We Write About When We Write about Ethics?

The term “ethics” comes pre-loaded with assumptions and associations that often lead people to the sort of impasses mentioned by David Foster Wallace: “Am I a good person? Deep down, do I even really want to be a good person, or do I only want to seem like a good person so that people (including myself) will approve of me? Is there a difference? How do I ever actually know whether I’m bullshitting myself, morally speaking?” (257). In an attempt to settle on a practical way to frame these debates, I have focused on how “ethics” might be discussed in WAC (Writing-Across-the-Curriculum) courses. One current option is to use the term “ethics” to refer to a prescribed code of professional conduct. This choice is more likely for students in fields that lead to some sort of licensing: graphic novels (or at least very reductionist versions of them) have already been recommended for use by students of medicine and law. Columbia University’s School of Continuing Education is developing a more innovative version of this process. It offers an M.S. in “Narrative Medicine,” and courses such as “Giving and Receiving Accounts of Self” focus on medical ethics while also reviewing texts by Henry James and Hannah Arendt and Judith Butler, as well as graphic texts such as Stitches (www.narrativemedicine.org). Other teachers have considered employing graphic novels (or other literary texts for that matter) as a redemptive means of building character or morals or making students “better people.” Scholars such as Martha Nussbaum have long argued that literature can and should have a crucial place in a society’s discussion of ethics. She is very direct in calling for the humanities to play a strong role in directing the moral development of today’s college students. As she states in “Compassionate Citizenship,” “Through stories and dramas, history, film, the study of philosophical and religious ethics, and the study of the global economic system, they should get the habit of decoding the suffering of another, and this decoding should deliberately lead them into lives both near and far” (3). Other scholars, such as Richard Rorty, are suspect of the over-arching narratives that govern the “moral work” that remains implicit in such ethical contexts. As Rorty claims, societies “might work better if they stopped trying to give universalistic self-justifications, stopped appealing to notions like ‘rationality’ and ‘human nature,’ and instead viewed themselves simply as promising social experiments” (193). I am not offering this statement as a one-sentence encapsulation of post-modernism, yet it may help to frame one basic issue facing teachers who try to introduce ethical terms into various assignments. Teachers who try to introduce and clarify traditional terms (perhaps “liberty” or “human rights”) may feel a sense of both urgency and hesitancy while doing so. If one invokes Derrida and places such terms sous rature (that is, liberty), or cordons them off inside quotations marks, or literally erases such terms from the board while teaching, then what replaces them? At the risk of generalizing about KCC students, many seem to prefer their metaphysics and universal values delivered without a chaser of irony or contingency. How then can one speak to students of “ethics” when the term calls forth so many different and contradictory meanings?

One particular statement from John Rothfork has helped frame the debate about the contentious status of post-modern ethics. His phrasing seems well-suited for describing how teachers negotiate the many and varied “contact zones” in their classes: “There is currently a fight in America over the operational logic or vocabulary which enables public or ethical discourse to proceed. The fight is over how we—as women, Native American Indians, Buddhists—talk about our ethical performative knowledge” (18). This search for an “operational logic” is indeed crucial, and the reference to “we” suggests how tenuous this process can become. In this case, Rothfork’s initial use of “we” seems to indicate a unified group, but the next phrase reminds us of our shifting and multiple allegiances. As I have read and re-read Rothfork’s statement, I’ve found it hard to isolate and name “the operational logic or vocabulary” that guides the “performative” aspect of ethical discussion (18; italics added). KCC students represent such a diversity of backgrounds that it seems more likely we’ll discuss pluralities—that is, “logics” and “vocabularies” rather than some singular and comprehensive term. When I do ask students to consider ethical questions, I’ve found that there are crucial places in graphic novels that leave us wondering about how this might be done, and both the students and I have found this to be problematic.

Writing the Ethical: An Assignment about a “Traditional” Novel

What might I consider to be a text which provides students with a challenging option for writing about ethics? My ENG 30 course usually features Edwidge Dandicat’s 2004 novel The Dew Breaker, a series of nine interwoven stories. The “dew breaker” is an unnamed 65-year-old Haitian immigrant who lives with his wife (Anne) and daughter (Ka) in East Flatbush near the Brooklyn Museum. A reader need not wait long to find that this man has committed and hidden horrific crimes—namely torturing and killing both political prisoners and completely innocent civilians—during the revolutions in 1960‘s Haiti. He had semi-confessed to some of his crimes to his wife years ago when their daughter was born. Now his secrets are causing all sorts of trouble. His daughter, an artist who had fully believed her father’s stories about being a political prisoner, has created an evocative sculpture in his honor that is about to be sold to a prominent Haitian TV star; his tenant in the basement apartment has recognized the “dew breaker” as the man who killed his parents years ago in Haiti; the Haitian community is openly seeking for retribution against the killers among them; a young college student and rookie journalist named Aline devoted herself to telling the stories of the victims of these crimes; his wife, who had found some consolation in prayer and faith, now believes that she is living a soul-destroying lie.

By the end of the book, there’s no clear resolution of the braided narratives sketched above, just a scenario in which every character must soon act, each knowing full well that most of these actions could lead to their own downfall. This ending, of course, presents a reader with much more than just a narrative “cliffhanger,” and in one of my writing assignments I ask the following:

During the final pages of the book, Anne is left wondering whether “reparation and atonement are possible”—and the book then ends without clarifying this for a reader. What do the terms “reparation and atonement” mean in general, and what specific meanings might these words have for these five characters in the book: Ka, Anne, Dany, Aline, and “the dew breaker” himself? Please analyze the varied responses of at least TWO characters. What key criteria or terms would seem most important to these characters? Please make sure to refer to specific scenes and/or statements from the book and to explain their significance.

Students generally do not find it hard to start a response, since the characters have often studied the contours of their own entrapments and silences. One story within the novel, “Book of Miracles,” features one scene that students often cite. Anne is in church for midnight Mass on Christmas Eve with her husband and daughter. During a moment when the entire congregation is hushed, Ka urgently whispers to her mother that she has spotted—or thinks she has spotted—a notorious torturer also known to be living a shadowy life in Brooklyn. Faced with the ethical dilemma of speaking or remaining silent, the two women frame their choices using very different vocabularies. Ka (who does not yet know of her father’s crimes) is furious, and barely restrains herself from shouting out. Anne is having other thoughts :

What if it were Constant? What would she do? Would she spit in his face or embrace him, acknowledging a kinship of shame and guilt that she’d inherited by marrying her husband. How would she even know whether Constant felt any guilt or shame? What if he’d come to this Mass to flaunt his freedom? To taunt those who’d been affected by his crimes? What if he didn’t even see it that way? What if he considered himself innocent? Innocent enough to go wherever he pleased? As a devout Catholic and the wife of a man like her husband, she didn’t have the same freedom to condemn as her daughter did. (81)

As the students reply to the essay prompt, I am not looking for a firm prescriptive answer about what a character should finally “do,” nor am I expecting that the students will take Anne or Aline or Dany’s dilemmas as a means of achieving some personal epiphany about their own ethical bearings. If I have any particular theoretical framework for my writing courses, it would be that of a socio-linguist, one who is intrigued and compelled by the “code-switching” that we all do while assuming various discursive roles. As James Paul Gee states in Social Linguistics and Literacies, “Any time we act or speak, we must accomplish two things: we must make clear who we are, and we must make clear what we are doing. We are each not a single who, but different whos in different contexts” (124). The conflicting arguments of Nussbaum and Rorty and Rothfork indicate that the ability to firmly define “ethics” remains elusive—yet the deep and recurring desire to try to share even a provisional public exchange of ideas about ethics is undoubtedly what keeps this conversation going at all. Which “vocabularies” are in play in The Dew Breaker, and just who is employing them? Might one start with Anne’s tortured silence as a believer and a cowardly co-conspirator? Or Ka’s hip art-school atheism and activism? Or Dany’s return to Haiti to learn how his parents’ pastoral community deals with their own members’ transgressions? Or the declarations of universal principles from human rights’ groups that are directly quoted in the novel? Or might it be Aline’s decision to look past her academic training as a journalist intern and to now write as an advocate for those “men and women chasing fragments of themselves long lost to others?” (137).

While dealing with texts such as The Dew Breaker, students usually can write their way into a fairly nuanced discussion of how ethical decisions can be shaped and informed by culture and language, by images and symbols, by legal codes and social customs. Traditional prose narratives often encourage this process. One reads of a character and notes how their ideas arise in a sequence, one that may not be quite rational and consistent, but one that has its own cadence, structure, phrasing, evasions, echoes. It is this process of speaking and restraining from speech, one that Dandicat calls “coded utterances,” that demands careful attention. How might a similar process take place while reading (and then writing about) a graphic novel? How might the reading of graphic novels complement, and perhaps complicate, the ways in which students read more traditional prose narratives? And finally, how might the reading of a graphic novel present students with a strikingly different perspective? For example, what if Dandicat’s description of Anne’s tormented self-examination featured few or no words? What if readers were presented instead with a few close-ups of Anne’s face and hands as she glanced again and again at the man she believed to be Constant? How might they write their way into a discussion of the ethical contexts for that moment?

Writing the Ethical: Assignments about Graphic Novels

“Every act committed to paper by the comics artist is aided and abetted by a silent accomplice” (68).

— from Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics

As we read Spiegelman’s Meta-Maus, students can work on various topics about trauma, about post-modern memory, about adapting and re-adapting, about the careful composition of every page. The publication of Meta-Maus, with its archival pictures and video and interview transcripts, allows students to see how memory is both retrieved and re-created in a survival tale. How then might students write about moments in a graphic novel when a character/person finds themselves at the edge of an ethical cliff?

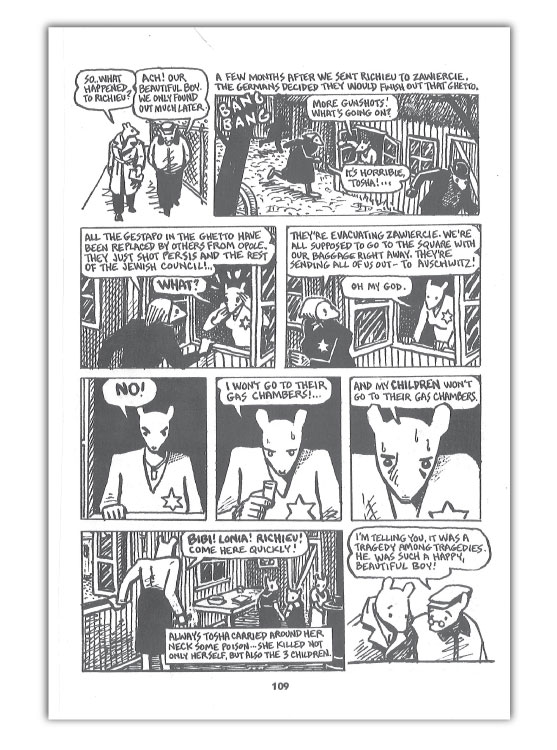

Maus certainly features many such moments. One obvious context for reading most “survivor tales” is that the author cannot rely too much on suspense. We all know from the start that Art Spiegelman and his father Vladek lived to tell this tale, so the question “Did they eventually survive?” is almost immediately displaced by the question “What did they do to survive?” and some version of its implicit corollary: “And did they lose their souls/compromise their dignity while doing so?” The latter chapters feature a series of almost unbearable decisions facing the Spiegelman family and their friends as they move from one “hole” to the other. In class, we generally focus on three distinct scenes. In the first, the Spiegelman family must decide whether to turn over their elderly relatives to the Nazis for deportation (or be taken away themselves); in the second, a group of Jews hiding desperately in a secret bunker must decide whether to kill a fellow Jew who has found them, and who may also be a Nazi informant. The third scene is given the most careful attention. The Nazis have overrun a town, and they are rapidly approaching the home of Vladek’s sister Tosha. She then faces a horrifying decision, as she must quickly decide whether to allow herself, her two young children, and her nephew Richieu (Art’s older brother) to be captured—or to poison herself and the children (109). Students often respond very strongly to these scenes when we discuss them in class, since they present such painful and irrevocable choices. Yet there are two recurring textual complications in many graphic novels that can pose difficulties for students who are writing about these texts. First, graphic novels often present crucial scenes by relying heavily on the use of verbal silence (or near silence) while emphasizing visual images; second, the deeper ethical dimensions of such scenes are suggested rather than discussed.

Students soon notice that Speigelman often uses relatively long and patiently detailed series of panels for seemingly minor events (Vladek’s complaints about his glass eye or his pills or Vladek’s joking with Anja about losing and finding a pillow during a refugee march) while retelling more disturbing events (the death of his own father or even the arrival at the gates of Auschwitz) in very terse and compressed sequences. Perhaps the most extreme example of this is the death of Tosha and Richieu, which Vladek calls the “tragedy among tragedies.” The entire sequence fills less than a page (see Image 1). It’s a very painful and evocative scene, and students are quick to notice how the elimination of details forces one to be attentive to what remains. For example, imagine the tone and volume of the word “NO!” Just note what her face and her collapsing shoulders convey as panels 5, 6 and 7 zoom in closer and closer. Or shudder as she quickly turns from the window, calls the children to her, and _______. (Dare we imagine the details of what follows?) It also challenges the whole premise of the book, that is, how one needs to both “retrieve” and “create” memory. (The news of Richieu’s death was gathered in fragments. Maus II mentions how Vladek and his wife Anja spend months after the war looking for Richieu, unaware of the scene described above.) When I’ve met students again in subsequent semesters, it is often that scene which has formed their sharpest recollections of graphic novels, of representations of the Holocaust, of “the creation of memory,” of our course in general.

Image 1: Maus

Yet can they then write about the scene’s ethical dimensions? For example, as we read Maus, we often read related scenes from Elie Wiesel’s Night, including one in which Wiesel considers throwing himself into a ditch filled with burning bodies. He does not, yet he is devastated to realize that the men around him are reciting the mourner’s Kaddish as they continue walking. Wiesel presents his ethical anguish in much bolder terms and closes this section with his famous invocation: “Never shall I forget that night…” While writing about that section, students often notice the seven repetitions of “Never,” the imagery of children being turned into “wreaths of smoke,” the implications of a “silent” sky, the despair which “murdered my God” (30-31). As one of their writing options, students are asked to consider the differences between these two types of texts:

COMPLEX COMMIX?: The graphic novel Maus obviously challenges a reader’s assumptions about whether a seemingly simple form can fully convey the complex emotions and ideas of people or characters. The book feature a series of scenes in which people must make very difficult ethical decisions. To what extent and in what ways might a graphic novel be more or less convincing or insightful than a traditional literary text while trying to represent the ethical conflicts of such scenes? You may refer to any of the texts we’ve read (or will read), or you may choose your own examples.

Here’s where a recurring issue has arisen–students often find it not just difficult but almost impossible to develop a sustained analysis of the ethical contexts for a scene such as the death of Richieu. It’s not that this moment lacks an ethical charge. Yet students have grave difficulties getting past the obvious points that Tosha has two horrifying options (infanticide and suicide vs. handing over herself and the children to face unspeakable violence) and that she is feeling desperate, hesitant, tormented, resigned. Students often struggle to provide an analysis which moves beyond these obvious points How might they move past their initial obvious statements, or, as I might ask in somewhat more technical terms, “What do you/we imagine to be in the gutter?” Don’t look at the text for some rain-filled trench–in the terminology of comics, the “gutter” refers to the literal/imagined “spaces” between panels or other distinct sections of the text, and as Scott McCloud says in his classic text Understanding Comics, “Despite its unceremonious title, the gutter plays host to much of the magic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics” (66). In this scene, the “gutter” between panels 7 and 8 seems especially resonant—the first panel features Tosha in near-collapse from the burdens now upon her, while in the next panel she has straightened up, wheeled around, and started an irrevocable act. “Gutters” get filled with all sorts of things besides basic assumptions about narrative continuity or what some comic artists simply call “closure.” Gutters invite us to fill them with allusions and voices-that is, they become intertextual. As teachers we may need to resist the urge to presume this knowledge of other texts and contexts that lead to a nuanced analysis. As an obvious example, a reference to suicide or infanticide may remind experienced readers of various characters and authors and texts: Hamlet, Sylvia Plath, Henry Scobie, Ernest Hemingway, Rebecca Harding Davis’ “Life in the Iron Mills,” Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Gwendolyn Brooks’ “The Mother.” Many literary associations may be unfamiliar, and even if they are, that brings up a further impasse. My students and I (and dare I say any other readers?) are the ones projecting these assumptions into the lacunae between these panels, rather than actually analyzing the contexts most crucial to Tosha. Might we be vaguely “right” while making certain assumptions about her doubts and terrors? Probably–but as I ask “What’s in the gutter?”, the ethical contexts generally become vague or even remain inaccessible.

One should not immediately be dismissive of the use of “silence” in a text, and many readers will already know of Foucault’s dictum that “There is not one but many silences.” However, for writers who are still struggling with the nuances of academic discourse, such “silences” in the “gutter” can lead to a lot of vagueness and potential confusion, and in courses where the development of precise language is so very crucial, this surely matters. Maus is surely not an isolated example, and it is almost chatty compared to Persepolis or Stitches. For example, a pivotal sequence in Persepolis depicts Marjane’s visit to the jail cell of her beloved Uncle Anoosh on the eve of his execution for being a political dissident. During this full-page sequence of panels, the two are alone in his cell—and Marjane says not a word (69). In Stitches, Small is a told a devastating truth about his place in his family—and this is followed by eleven pages (often referred to as the “rain sequence”) in which not a single word appears (257-268).Of course, this silence is an intentional effect, and an interview with David Small suggests a crucial distinction about visual and verbal communication. He notes, “I like to say that images get straight inside us, bypassing all the guard towers. You often go to the movies and see people with tears streaming down their cheeks, but you don’t see this in libraries, not in my experience at least.” He adds, “If told in words—even if I could have—the story would have lost that visceral impact” (2). Small’s memoir seems to both confirm and challenge some of the suggestions made in the previously cited article from The CEA Forum about assigning reading for non-majors. The text allows for students to find “relevance” in Small’s depictions of family, alienation, trauma, therapy, imagination, and a text that is able to “bypass the guard towers” often gives credence to deeply felt personal narratives. It can be used as a way to move from a “visceral” text to the more verbally oriented texts often found in academic disciplines. Yet teachers still need to be attentive about the “transferable writing skills” that non-majors might learn from these crucial sequences from texts such as Stitches. To be direct, what can we ask students about what Marjane and David are thinking in the sequences mentioned above? If there are “vocabularies” for their dilemmas, how might one know them and comment on them?

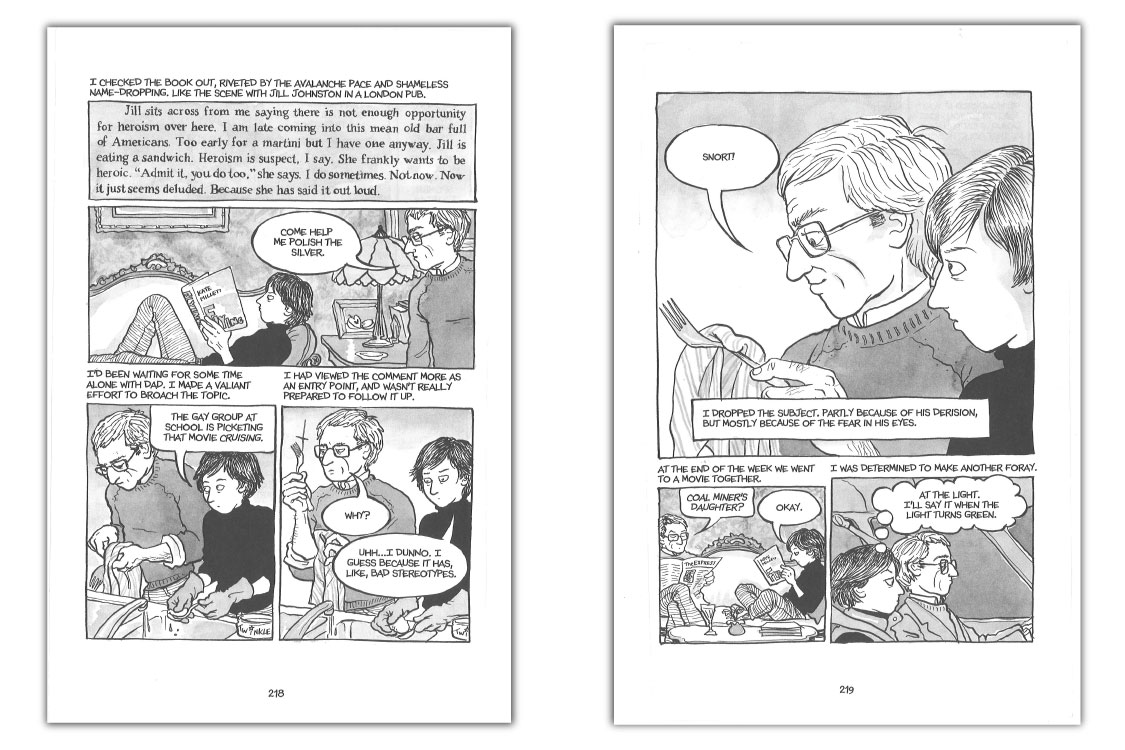

So could I name a graphic novel which might be less “evasive,” which might employ “gutters” in a way that allows for a fuller discussion of ethical discourse? I would suggest Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed 2006 memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. The book itself is all about evasion after evasion, primarily about how a closeted gay father and lesbian daughter “speak” of their own sexuality. Both seem to “know” that the other’s public identity is a shadow-play, but for the greater part of the book neither ventures to speak directly of their presumptions–instead, we read of their mumbling and code words and knowing glances. Above all, father and daughter “speak” through books, some given as gifts that seem more like invitations for dialogue, others that are discussed in English courses, others used to suggest what cannot yet be said. Toward the end of the book, Bechdel becomes increasingly aware that these silences are not just awkward but damaging, and she resolves to speak out. A crucial exchange appears on pages 218-219 (see Image 2). In a panel near the top of the page 218, Alison is lying on the couch as her father approaches and asks her to help polish some silver. While in the kitchen they have yet another failed dialogue about the movie Cruising, and the scene could easily be read as a pair of missed chances—the chance for Alison to speak, and the chance for readers to know more of what Alison is really thinking. It should be noted that none of the four books I’ve mentioned use extended dialogues, and nor do the vast majority of graphic novels; often this choice isn’t a rejection of dialogue but simply a recognition that the visual format of most graphic texts simply does not leave much space for verbal exchanges. Also, while memoirs rely heavily on voices, the voices of Vladek Spiegelman, Taji Satrapi, the Small family, and Bruce Bechdel are generally terse and understated. The key difference is that the “gutters” of Fun Home are like over-flowing baskets of interior monologue and literary allusion. Neither of these terms is really adequate here. “Interior monologue” is a barren label for a memoir in which self-conscious over-writing appears on almost every page. Readers need to engage with lines such as “I was adrift on the high seas, but my course was becoming clear. It lay between the Scylla of my peers and the swirling, sucking Charybdis of my family” (213). These brief allusions are often paired with lengthy and direct quotations from writers such Proust, Fitzgerald, Wilde, Joyce, and so many others, which in turn may be contrasted with both images and text from movies, letters, album covers, news headlines, dictionary entries, and her own somewhat neurotic diary. The effect of these methods is that they allow for a much more substantial discussion of an ethical issue.

Image 2: Fun House

To be honest, my description of the previous dialogue was intentionally incomplete. Before the conversation starts, Bechdel adds a key reference. As her father is talking, Alison is reading a section of Kate Millett’s Flying, and this excerpt is quoted in full:

Jill sits across from me saying there is not enough opportunity for heroism over here. I am late coming into this mean old bar full of Americans. Too early for a martini but I have one anyway. Jill is eating a sandwich. Heroism is suspect, I say. She frankly wants to be heroic. “Admit it, you do too,“ she says. I do sometimes. Not now. Now it just seems deluded. Because she has said it out loud.

This brief excerpt from Millett introduces the themes underlying the strained conversation that follows: the desperate need to speak, the desire or fear of the “heroism” that this entails, the rising tension between “now” and not now,” the choppy declarations and the continued retreats into a veiled silence. All of these are given resonance, so that even Bruce Bechdel’s derisive “Snort!” becomes significant (219).

Non-majors who are becoming familiar with reading more complex literary texts can also learn a great deal about the form of an ethical argument or question simply by analyzing the ways in which Bechdel challenges the very idea of a “page.” In some ways, pages 100-101 are not that surprising: a splash page features a photograph overlaid by eight distinct text boxes containing questions, captions, and loose associations. The photograph is of a young man named Roy who had often done both child-care and landscaping for the family. Yet the underlying question is surely a resonant one: why would her father have taken—and kept—a photograph of Roy lying almost naked on a hotel bed? What was the father trying to reveal or conceal? What may she as an author now assume or reveal about her father’s semi-hidden past? The answers are neither immediate nor conclusive. Instead, the text boxes are arranged almost chaotically, both forcing and allowing a reader to create some sort of logical sequence—or a variety of sequences. In David Small’s terms, the image of Alison’s hand holding this picture does “bypass all the guard towers” and create a very “visceral” response while also using the text boxes to voice themes that echo throughout the book. As the “final” text box states, “In an act of prestidigitation typical of the way my father juggled his public appearance and private reality, the evidence is simultaneously hidden and revealed” (101). Bechdel provides a suggestive—but far from prescriptive—context for judging her father’s life and her own reactions, and this sort of context is quite helpful for writers who are still trying to learn academic discourse. The following is a writing question I use about Fun Home, one based loosely on the prompt that I use about The Dew Breaker:

One of the most pressing issues in contemporary society is that of being “silent.” What are some situations in which being “silent” develops into a complex ethical dilemma? Please refer to the choices of TWO or more people from Fun Home. How and why do they remain “silent?” What, if anything, do they reveal about their silence, how do they reveal it, and what conflicts arise from such revelations? Please make sure to refer to specific scenes or statements from Fun Home (and/or other texts you’ve read) and to explain their significance.

In this case, students have ample options besides projecting personal associations into the “gutters” of Fun Home. In academic terms, the students now have more than compelling visual imagery–they also have complex verbal contexts for the sort of investigation that one would hope they will engage in as they take Introduction to Literature. (Or as Spiegelman would say, they have “commix” to draw upon.) Whether the scenes from Bechdel rely on relatively straight-forward bits of narration or on more intertextual references, the students have a much fuller opportunity to write and to analyze, while also reading a very bold, timely and innovative text!

“Deep Thinking” and Honest Questions

“There is no philosophical area that cannot potentially be given a graphic novel treatment” (49).

— from Jeff McLaughlin’s “Deep Thinking in Graphic Novels”

Perhaps I have wound up arguing that graphic novels are best at confronting ethical quandaries when they rely upon seemingly traditional fictional techniques such as dialogue and narration. If that does wind up to be the case, then that might prove to be unhelpful, since there are not many graphic novelists who use the densely allusive verbal references and echoes of Fun Home.8 Of course, those who prefer to use traditional prose texts in a Literature course can find ample support for that choice. One might start with Mark Kingwell’s claim that “On Cartesian principles, we cannot directly know the mind of another; but words printed on a page give us the best possible chance at coming close, better even than interacting with others” (5; italics added). It would seem obvious that graphic artists would soundly reject this premise, and the scholarly articles cited earlier generally presume that this notion of “the best possible chance” is exactly what graphic artists are trying to usurp. However, I was surprised by a comment from Scott McCloud about “gutters” and “closure.” As he states, “Closure in comics fosters an intimacy surpassed only by the written word, a silent, secret contract between the creator and audience” (69; italics added) Consider the various “gutters” that were discussed above. When Tosha turns to face the children, when Marjane sits silently in a jail cell, when David withdraws into his own drawings, when Alison’s attempt to speak is met with “Snort!,” there surely is an “intimacy” created. What can one say about moments? As Kingwell reminds us, this question may be merely speculative, since directly “knowing the mind” of another simply can’t happen. Yet we can at least glimpse a tentative map of that interior by reading what our students write, and if they can’t write much about Tosha’s last thoughts, for example, then perhaps that “intimacy” remains hesitant and amorphous; it is often one based primarily on personal assumptions rather than textual analysis.

What then might teachers keep in mind as we ask students to write about situations that demand a consideration of ethical issues while also denying readers many of the narrative techniques (such as dialogue, omniscient narration, interior monologue, allusion, etc…) that they may expect to find? If readers, especially those who may be still learning the basics of college-level academic discourse, must rely instead on a great deal of inference based on non-verbal cues, then what are some possible compromises that arise, and how might teachers work through these compromises? It might seem to be petty and even self-defeating to raise such challenges when I’ve already decided that graphic novels have much to contribute to the study of reading and writing–of course, one could just settle for the obvious disclaimer that there is no form/genre that lends itself to all types of writing assignments. Yet in discussions among fans and scholars of graphic novels, there remain nagging doubts, and students surely are not shy about sharing their own suspicions. During the sequence of lessons on Maus, I ask them to do an in-class assignment based on Daniel Correia’s article “A Novel Idea,” in which he asks students and teachers at the University of California at Santa Cruz for their thoughts about reading graphic novels in Literature courses. Most of the article’s commentators are supportive, and some of them even read graphic novels as their own academic declarations of independence. The students are also quick to note a section of the article in which a graduate student named David Namie expresses the reservations that he and some of his students had. As Correia explains:

“Namie admitted that his students found something lacking in the graphic novel he used for his course. ‘Although there wasn’t resistance to the idea of reading a graphic novel, there was the feeling that something wasn’t there,’ Namie said. ‘Students expect more substance or something more intellectual from traditional texts like Wuthering Heights.’” (4)

There are usually a few critical students who agree with him, but the obvious problem is that claims about “something lacking” or “something wasn’t there” or “something more intellectual” can sound suspiciously like the disengaged comments given by someone who doesn’t care for cricket or rap. I am not trying to shame Namie or my students here—I have been fumbling around with my own phrasing for awhile as well. So I have arrived at the tentative conclusion that this absent “something” is not about the five reasons that I mentioned at the beginning of the essay. It is not about literacy or identity or meta-narratives or visual culture or post-modernism–the elusive “something” seems to be the ethical dimensions of reading and writing about such texts.

For the many reasons that I outlined earlier, I will be teaching graphic novels again in ENG 30. I will keep in mind Jeff McLaughlin’s article, while also be questioning his basic assumption. There are fascinating things that one can find in the “gutters” of graphic texts, but a fully realized “examination of ethical issues” remains an elusive one. Of course, McLaughlin is careful to qualify his statement with the word “potentially”–and the “potential” of graphic novels to do so many others things is quite strong. When a graphic novel such as Fun Home allows for such a discussion, I will be glad to encourage it, but I will also be wary of assigning students to make such “examinations” of ethical dilemmas when I find myself having trouble doing so.

Endnotes

[1] Many writers and teachers have noted the inadequacy of this term. Many graphic “novels” are actually non-fiction memoirs, and others read more like novellas or short stories. Many have little similarity with more traditional definitions of the “novel.” Yet it remains the most commonly-used term to refer to texts such as Maus, so I will use it for convenience. For a fuller discussion of this issue, see Hatfield, “Defining Comics.”

[2] For a basic review of literacy issues, see Schwarz, “Expanding Literacies.”

[3] More specialized uses of graphic novels can be found in MacDonald, “Hottest Section in the Library,” and Smetana, “Using Graphic Novels.” Also see Redford, “Graphic Novels Welcome Everyone,” and Gerde and Foster, “X-Men Ethics.”

[4] For an overview, try Aldama’s Multicultural Comics and Royal, “Introduction.” For more focused discussions, see Boatwright, “Graphic Journeys” and Squire, “So Long As They Grow Out of It.”

[5] McCloud’s Understanding Comics is a classic tour of these innovations. Also see Almond, “Deconstructed—Chris Ware’s Innovation.”

[6] Courses that analyze visual culture are proliferating. Simply google “CUNY courses on visual culture” for a sampling. See Drucker, Graphesis for broader contexts.

[7] See Roeder, “Looking High and Low”; Chute, “Comics as Literature.”

[8] Readers might try Joe Sacco’s Safe Area Gorazde: The War in Eastern Bosnia or the obscure Gemma Bovary by Posey Simmonds or even Radioactive: A Tale of Love and Fallout, Lauren Redniss’ stunning graphic biography of Marie Curie. Of course there remains Alan Moore’s classic V for Vendetta, which has enough allusions and speeches to keep a graduate seminar busy. Moore’s Watchmen is even more complex, and gives preferences to long-winded dialogues rather than subtle silences; as a colleague once remarked to me, this text doesn’t have “gutters,” it has canyons of highly self-conscious prose interspersed among the graphic passages. Yet these texts are the exceptions, and many recent graphic novels are featuring less and less dialogue and/or interior monologue.

Works Cited

Aldama, Frederick Luis, ed. Multicultural Comics: From Zap to Blue Beetle. U of Texas P, 2010. Print

Almond, Steve. “Deconstructed–Chris Ware’s Innovation.” New Republic 13 (Dec. 2012): 1-3. Print.

Amicucci, Ann. N. et al. “‘You are asking me to do more than just read a book’: Student Reading in a General Literature Course.” The CEA Forum 44, 1 (Winter/Spring 2015): 1-29. Print.

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Houghton Mifflin, 2006. Print.

Boatright, Michael D. “Graphic Journeys: Graphic Novels’ Representations of Immigrant Experiences.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 53 (March 2010): 468–476. Print.

Chute, Hillary. “Comics as Literature: Reading Graphic Narrative.” PMLA 123, 2 (2008): 452–465. Print.

Program in Narrative Medicine. Columbia University Medical Center. www.sps.columbia.edu/narrative-medicine. Accessed 15 Jan. 2016.

Correia, Daniel. 2007. “A Novel Idea.” City on a Hill Press www.cityonahillpress.com/2007/02/08/a-novel-idea. Accessed 20 Dec. 2015.

Dandicat, Edwidge. The Dew Breaker. Vintage, 2004. Print.

Drucker, Joanna. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Harvard UP. 2014. Print.

Gee, James Paul. Social Linguistics and Literacies. Routledge, 1996. Print.

Gerde, Virginia W. and R. Spencer Foster. “X-Men Ethics: Using Comic Books to Teach Business Ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics Vol. 77, No. 3 (Feb., 2008): 245-258. Print

“Getting Graphic: Using Graphic Novels in the Language Arts Classroom.” http://gettinggraphic.weebly.com/index.html. Accessed 12 Aug 2014.

Hatfield, Charles. “Defining Comics in the Classroom.” Teaching the Graphic Novel. Stephen E. Tabachnick, ed. Modern Language Association, 2009. Print.

MacDonald, Heidi. “How Graphic Novels Became the Hottest Section in the Library.” www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/libraries/article/57093-how-graphic-novels-became-the-hottest-section-in-the-library.html. 3 May 2013. Web.

McCloud, Scott. “Blood in the Gutter.” Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper, 1993. Print.

McLaughlin, Jeff. “Deep Thinking in Graphic Novels.” The Philosophers’ Magazine Vol. 60 (2013): 44-50. Web.

Nussbaum, Martha C. “Compassionate Citizenship.” Commencement Address. Georgetown University. http://www.humanity.org/voices/commencements/martha-nussbaum-georgetown-university-speech-2003. Accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

Redford, Kyle. “Graphic Novels Welcome Everyone into the Reading Conversation.” The Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity. http://dyslexia.yale.edu/EDU_GraphicNovels.html. Accessed 25 Aug 2014.

Roeder, Katherine. “Looking High and Low at Comic Art.” American Art. 22, 1 (Spring 2008): 2-9. Print.

Rorty, Richard. Essays on Heidegger and Others: Philosophical Papers, Vol. 2. Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Rothfork, John. “Post-Modern Ethics: Richard Rorty and Michael Polanyi.” Southern Humanities Review 29.1 (1995): 15-48. Print.

Royal, Derek Parker. “Introduction: Coloring America: Multi-Ethnic Engagements with Graphic Narrative.” MELUS (Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States) 32 (2007): 1-16. Print.

Schwarz, Gretchen. “Expanding Literacies Through Graphic Novels.” The English Journal 95 (2006): 58-64. Print.

Small, David. Interview. amazon.com. Accessed 15 Jan 2016.

David.Smetana, Linda et al. “Using Graphic Novels in the High School Class: Engaging Deaf Students with a New Genre.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy (2009): 228–240.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Pantheon, 1986. Print

Speigelman., Art. Meta-Maus: A Look Inside A Modern Classic. Pantheon, 2011. Print.

Squier, Susan. “So Long as They Grow Out of It: Comics, the Discourse of Developmental Normalcy, and Disability.” Journal of Medical Humanities 29 (2008): 71-88. Print.

Wallace, David Foster. “Joseph Frank’s Dostoyevsky.” Consider the Lobster and Other Essays. Back Bay Books, 2006. Print.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. Print.

Author Bio

Gene McQuillan is a Professor of English at Kingsborough Community College (the City University of New York) where he has taught since 1993. His writings and teaching have often focused on various forms of non-fiction, and he has published articles on travelogues, natural history, memoirs, and graphic novels. He has also published a series of articles on contemporary narratives about the Human Genome Project. In 2006, he served as the President of the Mid-Atlantic Popular/Culture Association (MAPACA). He is currently the co-facilitator of a FIG (Faculty Interest Group) at KCC that focuses on “Graphic Novels, Cartoons, and Comics.”

Reference Citation

MLA

McQuillan, Gene. “Looking in the ‘Gutter’ for Ethical Questions: Reading and Writing about Graphic Novels.” 2018. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy vol 5. no 1. http://journaldialogue.org/issues/v5-issue-1/considering-ethical-questions-in-nonfiction-reading-and-writing-about-graphic-novels/

APA

McQuillan, G. (2018) Looking in the ‘gutter’ for ethical questions: Reading and writing about graphic novels. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy. 5(1). http://journaldialogue.org/issues/v5-issue-1/considering-ethical-questions-in-nonfiction-reading-and-writing-about-graphic-novels/

Academia.edu

Academia.edu