The Coronavirus Crisis Highlights our Vulnerabilities

Bridget Goodman

Nazarbayev University

Astana, Kazakhstan

bridget.goodman@nu.edu.kz

Image 1: A flyer from the New Jersey Coalition for Inclusive Education thanks participants and shares links to resourcesdeveloped for parents and educators as they transition to online teaching. https://twitter.com/NJCIE/status/1243652229388697600?s=20

In my previous column, I twice referred to “vulnerable” populations—the medically vulnerable, and small businesses, each of which in their own way may be at risk for succumbing to this pernicious virus. The reality is that these are just two examples of needs that are made more visible by this epidemic.

First and foremost, though, we have to make sure we are not discussing those with underlying medical conditions (as the new English-language discourse goes) and other vulnerabilities from an ableist view that sees any form of difference in ability as foreign, i.e. “other” (see also CohenMiller, 2019), a burden, or a sign that people are expendable. Even in writing this article I had to edit myself to write not about “challenges” but about “needs” to avoid a problem-oriented view. As Makoelle (2020) has pointed out, the goal of inclusion in education is to move away from views of ability as problem, deficit, barrier, or correction to “pedagogy that advocates education for all…not only disability but also aspects such as socioeconomic status, language differences, religion, culture, gender, ethnicity, and others” (p. 7).

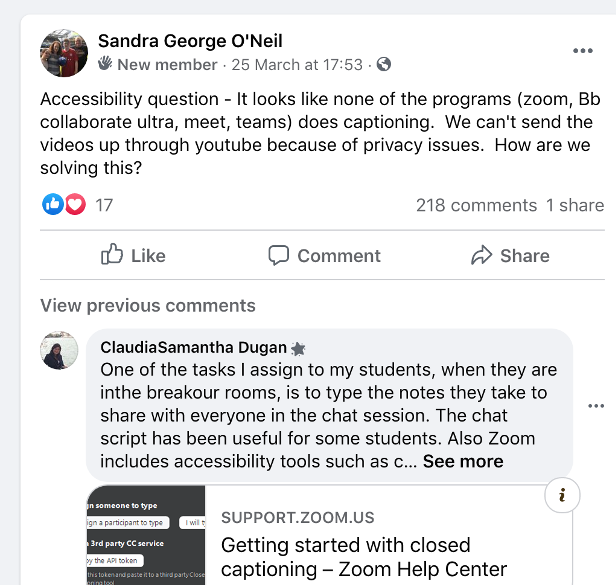

As I scroll through my Facebook and Twitter feeds, I am heartened by the signs that the media and educators are talking proactively about the impact of coronavirus and educational changes on students with this array of backgrounds, and working constructively to share ways of addressing specific student needs. The needs of students typically labeled “special needs” still catches my attention first. In the Facebook group the Higher Ed Learning Collective, here is one example of a post about how to ensure Deaf students accessibility to information in online learning platforms. In this post (see image 2 below), Sandra asks how to solve the question of providing closed captioning in the currently used teaching platforms (Zoom, Blackboard, etc.). She further rules out using YouTube because of the institutional view that there is not sufficient privacy for students–another vulnerability talked about more in social media these days. There are 218 responses, including one from Claudia who offers both alternate pedagogies and a link to Zoom support on how to start using closed captioning in Zoom.

Image 2: Accesibility question retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/groups/onlinelearningcollective/?post_id=547571822540187

In the field of multilingual education and multilingualism, the focus is on access to information and to equitable education for those who do not speak the dominant language of society or the primary language of instruction. There is an expressed need to ensure that adults who speak a minority language have access to information about coronavirus in their native language. I have seen posts on Facebook from language groups calling for translators, or asking people to share the translation of the phrase “wash your hands” in different languages–though I wish they would write it more fully as “wash your hands for 20 seconds with soap and water”. A recent blog in Edweek highlighted the individual “barriers” and structural inequalities in providing education online to English language learners, but also showed how state and national organizations are marshaling resources to meet English language learners’ needs.

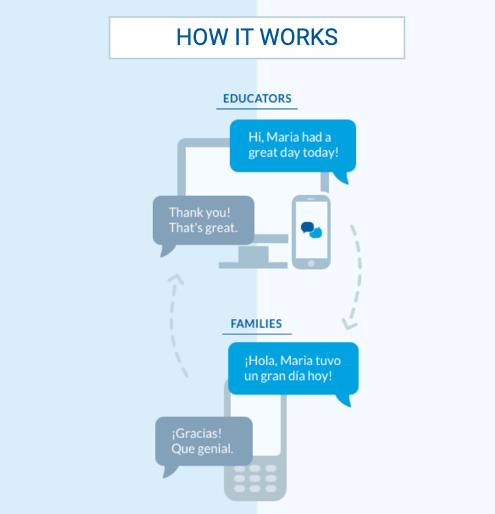

An email forwarded to me recently indicated there is now a (temporarily) free service which offers two-way mobile communication between teachers and parents in over 100 languages. The image on the Talking Points website (see image 3 below) demonstrates how the service works. The teacher can send a text message to a parent in English, which is translated by Talking Points in the parents’ home language–in this example, Spanish. The parent reads the text in Spanish, and replies in Spanish, while the teacher receives the text in English.

Image 3: Talking Points on two-way mobile communications retrieved from https://talkingpts.org/

In terms of socioeconomic status, multiple Facebook and Twitter posts from the U.S. context have pointed out that many children depend on schools for free or reduced-price lunches. In response, school districts in California and other states are still offering lunches to students that can be picked up and taken to go. I should note that having to go out and get lunch, especially for families that may not have private transportation, may increase not only nutrition but also exposure risk and general anxiety. This can be linked more broadly to concerns raised about students’ mental health. Individuals already prone to depression or anxiety may have symptoms exacerbated by increased social isolation. Below is one of the top posts on Twitter about the need to balance new forms of education with maintaining students’ mental health (see image 4). Queerantine, in words and with the image of a pug dog wrapped in a blanket, laments the decision to continue assigning homework during a “damn pandemic???”. Queerantine ponders, “do they not know they’re only adding to their students’ debilitating anxiety? or do they just not care?”

Image 4: Queerantine pup dog wrapped in a blanket retrieved from https://twitter.com/FeelingFisky/status/1241161915214082049?s=20

The 22 comments on this post talk more generally about the pressure on teachers from the administration to continue learning. They suggest measures to reduce anxiety by reducing assessment expectations—i.e. giving all As, marking assignments pass/fail, or making assignments ungraded altogether. Only one approach takes an ableist view: “do people not understand that life and the economy have to go on?”.

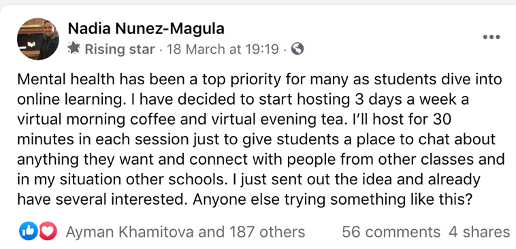

There is some evidence of teachers saying they are putting students’ wellbeing first. In this Facebook post (see image 5) which got 187 likes and loves on the online learning collective, Nadia starts by saying “mental health has been a top priority for many as students dive into online learning”. She describes her solution, which is to host virtual morning coffee and evening tea three times a week to give students a “place to chat” and connect”.

Image 5: Mental health Tweet retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/groups/onlinelearningcollective/?post_id=543121986318504

Nearly all of the 56 comments indicate general and enthusiastic support for this approach, suggesting platforms for hosting spaces to share and chat. The remaining comments were focused on getting students to respond at all. One posted a link I have also shared on Twitter from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Granted, the social issues outlined above were present before the virus hit, and it could be argued that the educators and organizations now responding to these issues were already predisposed to consider and address student needs in an inclusive way. What’s important here, I would argue, is representation. It’s the recognition that while the ‘pan’ in ‘pandemic’ means ‘all’, it does not mean “universally the same”. As educators, we can see the diversity of needs under this rainbow and continue to think now and in the future about how to continue to see and serve.

In closing, let me say in these times, we as educators also have to find new ways to face our own vulnerabilities. I may have to acknowledge to my students that this is hard and sad and scary for me sometimes too. Now I am the one who is going to sometimes miss deadlines as I deal emotionally with the latest developments on the virus, navigate new shutdowns of daily life, check in on friends and family near and far away, or just need extra time to curl up on the couch with Netflix and my dwindling supply of popcorn before grading that final assignment. But maybe as we allow ourselves to be vulnerable; we create a safer space for our students to be vulnerable and together develop a stronger mutual support system.

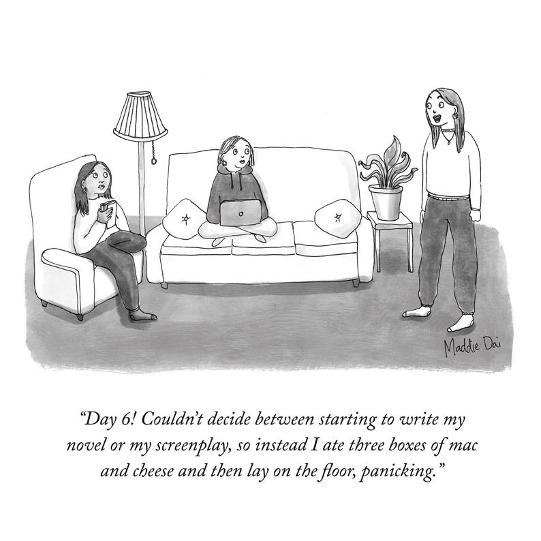

Image 6: A New Yorker cartoon by Maddie Dai shows three people in a living room, and a desire for writing productivity that turned instead into a panic eating session, “Day 6! Couldn’t decide between starting to write my novel or my screenplay, so instead I ate three boxes of mac and cheese and then lay on the floor, panicking.” https://twitter.com/maddiedai/status/1242129074748866562?s=20

References:

CohenMiller, A. S. (2019). From the news to zombies: Teaching and learning about Otherness in popular culture. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy. 6(3). www,journaldialogue.org/issues/v6-issue-3/teaching-and-learning-about-otherness-in-popular-culture/

Makoelle, T. M. (2020). Language, terminology, and inclusive education: A case of Kazakhstani transition to inclusion. Sage Open, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020902089

Author Bio:

Bridget Goodman is Assistant Professor and Director of the MA in Multilingual Education Program at Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, Astana, Kazakhstan. Her teaching and research interests include: the use of the first language (L1) in second and foreign language classrooms, language policy, and sociolinguistics in post-Soviet countries.

Academia.edu

Academia.edu