Teaching High School Students to Recognize Problematic Narratives

B Mann

Léman Manhattan Preparatory School

Manhattan, NYC, United States

b.mann@lemanmanhattan.org

Meg Greenberg Sandeman

Léman Manhattan Preparatory School

Manhattan, NYC, United States

m.greenberg@lemanmanhattan.org

During the 2018-2019 academic year, racist incidents at three New York City private schools garnered mainstream media attention. The New York Times published a series of articles including “Blackface Video Has Elite New York Private School in an Uproar” (Jan. 20, 2019) and “Video with ‘Racist and Homophobic’ Language Surfaces at Elite Private School” (Feb. 25, 2019). The following month, “Racial Controversy Engulfs a Third Elite NYC Private School” appeared in the New York Daily News (March 3, 2019). The authors of each of the three headlines seem to suggest that racist and homophobic incidents are a surprising phenomenon in an urban independent school setting. Herein lies the problem.

We are an Upper School librarian and an Upper School English teacher at a New York City private school. As educators, we know racism and homophobia are systemic, and that the work of deconstructing problematic narratives is ongoing, even in progressive institutions. To this end, we have developed a lesson, “Problematic Narratives,” to model an inquiry-based approach to identifying and interrogating harmful cultural messages. We deliver this lesson to ninth graders at the start of the academic year in order to facilitate the development of critical thinking skills foundational to the formation of a social justice lens and to increase meaningful engagement with curricular texts.

The specific aim of the lesson is to teach students to critically analyze texts by uncovering stereotypes in the media they consume. While critical media literacy is not always part of the traditional English Language Arts curriculum, we find our students become highly invested when they are made responsible for discussing the issues pertinent to their lives through the television shows, films, and advertisements they already know well. Our high school students frequently express identity through attachment to popular media and fandom and incorporating the opportunity to analyze their favorite media into a lesson early in the school year sets the tone of the classroom environment. Early close collaboration with the librarian allows students to not only begin to think about the librarian as an academic resource, but also to develop confidence in speaking openly with another adult in the community about identity and representation.

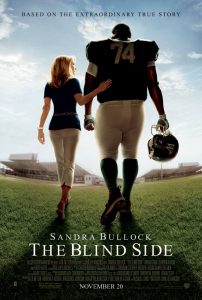

Before asking students to present a problematic narrative from a popular media text of their choice, we deliver two mini-lessons. The first involves showing a trailer for The Blind Side (2009), in which Sandra Bullock’s white character adopts a black student who attends her children’s school (see Image 1). The plot of the film is loosely based on the biography of Leigh Anne Tuohy and her involvement in Michael Oher’s life before his NFL football career. After viewing the trailer, multiple students routinely comment that Sandra Bullock’s character is an ally to Michael and that the movie seems like a neutral portrayal of a woman who is a caring member of her community.

Image 1: The Blind Side Movie Poster

We then distribute a graphic organizer with questions we have adapted from Abesha Shiferaw’s “How to Tell Compelling Stories While Avoiding Savior Complex and Exploitation” to introduce the concept of the white savior narrative. Students are asked to work in pairs to answer: How does Leigh Anne Tuohy’s identity show up in the story about Michael Oher?; Should she be the one telling this story, or can someone else?; Is Michael Oher’s consent informed? (Did he know how his story would be used?); Do the writers and directors oversimplify the story?; Do the writers and directors perpetuate existing narratives about vulnerable or marginalized people and communities? We review the terms Shiferaw uses, so students have a working definition of consent, exoticize, perpetuate, stereotype, tokenize, and marginalize. In a subsequent discussion, students volunteer adjectives to describe Leigh Anne Tuohy and Michael Oher. They note she is portrayed as a wealthy, thin, white woman who wants to rescue Michael, and he is portrayed as a poor, overweight, young black man who struggles academically. Students begin to argue that the story might be more interesting if it had been told from Michael Oher’s perspective. We ask students to investigate Oher’s reaction to the release of the film, and they find articles such as Linda Holmes’ “Beyond ‘The Blind Side,’ Michael Oher Rewrites His Own Story” (Feb. 8, 2011), published by NPR, and David Newton of ESPN’s “Michael Oher Gives Negative Review to Effect ‘The Blind Side’ Has Had” (June 18, 2015). The discovery of these articles leads to conversations about what constitutes consent. We then help students to frame their interpretation of the film by explicitly teaching the concept of the white savior narrative, in which a story that could focus on the experience of a person of color instead revolves around the experience of an external white character. This white character plays a helping role to the person of color and undergoes a personal transformation as a result. After this introduction to the concept, students are able to think of other examples of texts that adopt this problematic narrative.

In the second mini-lesson, we introduce the concept of signaling to enable students not only to recognize who should be telling a story and how it should be told, but also why stereotypes are employed in texts. We use characters from familiar Disney movies to illustrate how creators signal their audience to feel a particular way about a character by drawing on stereotyped characteristics, including race, gender, and body type. We start by showing students an image depicting an array of Disney princes, and contrast it with a line-up of Disney villains. Students note that the princes uniformly have large arm muscles and broad shoulders that taper into a “triangle body,” while most villains have long thin faces and at least one physical attribute that markedly differentiates them from having the “prince” body type. We review images from several classic Disney films, highlighting the distinct physical attributes of the prince, villain, and sidekick characters. Students take full responsibility for identifying the characteristics in the later examples and demonstrate that even if they have not seen a particular movie, they can quickly identify the character archetypes.

Once students have a strong grasp of signaling as a concept, we discuss that it is used to convey information quickly by referencing and reinforcing dominant cultural narratives that have real and harmful consequences for many people. Through discussion, students develop the ability to articulate that there is something jarring about Disney’s uniform portrayal of a male protagonist with a buff “triangle body.” They are led to understand that the popular media’s constant reinforcement of the idea that a hero has a particular build produces and cements a harmful physical hierarchy.

We encourage students to spot patterns in texts, or media, that do not make sense or do not match their experience of the world and to interrogate these patterns until they arrive at the underlying cultural message. For instance, we ask questions including: Why would the writer/director of The Blind Side have chosen to represent a white woman rescuing a young black male athlete? Why would every Disney prince have the same body type if we know that men have all different body types in real life? What values are the creators assigning to this set of physical characteristics? In reference to the texts explored in both mini-lessons, we ask: How do these values connect to dominant cultural narratives, and who benefits from/is harmed by these narratives?

Once we complete the mini-lessons, we ask students to work in pairs to choose a film, television show, or advertisement containing a problematic narrative and to share their findings with the class (See Table 1). They are required to show a clip, a passage from a text, or images of the chosen advertisement. Students are again given a graphic organizer with the modified questions from Shiferaw’s article to help them to structure their argument. They are also asked how and why the creators of the text signal dominant cultural narratives. As it is our hope that the discussions will be intrinsically motivating, we do not grade the assignment.

We strive to build a classroom community prepared to engage with issues of social justice. The series of activities presented in this lesson can equip students with the tools they need to become more aware of how problematic narratives show up in their daily lives and to enact change in the school environment, one conversation at a time.

| Table 1: Texts our students have chosen to demonstrate problematic narratives |

| Body Image, Sexist Stereotypes and Consent

Bring It On “Blurred Lines” Brandy Melville clothing company Clueless Grease Insatiable Legally Blonde Shallow Hal Sixteen Candles Racist Stereotypes and Colorism Skin lightening products Soap and detergent commercials Rescue Narrative The Little Mermaid Shrek Super Mario Brothers Video Game Twilight Stigma associated with Mental Health and Glorification of Suicide Thirteen Reasons Why YouTube Influencers White Savior Narrative Avatar Green Book To Kill a Mockingbird |

Works Cited

Shiferaw, Abesha. “How to Tell Compelling Stories While Avoiding Savior Complex and Exploitation.” Rainier Valley Corp, 4 April 2018, rainiervalleycorps.org/2018/04/tell-compelling-stories-avoiding-savior-complex-exploitation/. Accessed 26 Aug. 2019.

Warner Brothers. “The Blind Side Movie Poster.” Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., n.d., warnerbros.com/movies/blind-side/. Accessed 26 Aug. 2019.

Author bios:

Meg Greenberg Sandeman is a high school English teacher at Léman Manhattan Preparatory School.

B Mann is a middle and high school librarian and transgender educator at Léman Manhattan Preparatory School.

Reference citations

APA

Mann, B and Sandeman, M. G. (2020). Teaching High School Students to Recognize Problematic Narratives. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy, 7(1). http://journaldialogue.org/musings/pedagogy/teaching-high-school-students-to-recognize-problematic-narratives/

MLA

Mann, B and Meg Greenberg Sandeman. “Teaching High School Students to Recognize Problematic Narratives.” Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Popular Culture and Pedagogy, vol. 7, no. 1, 2020, http://journaldialogue.org/musings/pedagogy/teaching-high-school-students-to-recognize-problematic-narratives/

Academia.edu

Academia.edu