When the Crisis Hits Home: Helping Students Cope with Illness and Death

Bridget Goodman

Nazarbayev University

Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan

bridget.goodman@nu.edu.kz

In the previous three columns, I highlighted ways in which social media is providing resources, platforms, and inspiration to continue to educate our students and/or our children during this pandemic. The presentation of these offerings has been driven by my view, influenced in part by early positive reports out of China, that continuing to teach online can provide structure and a sense of “normalcy” to students and teachers who are forced to remain at home.

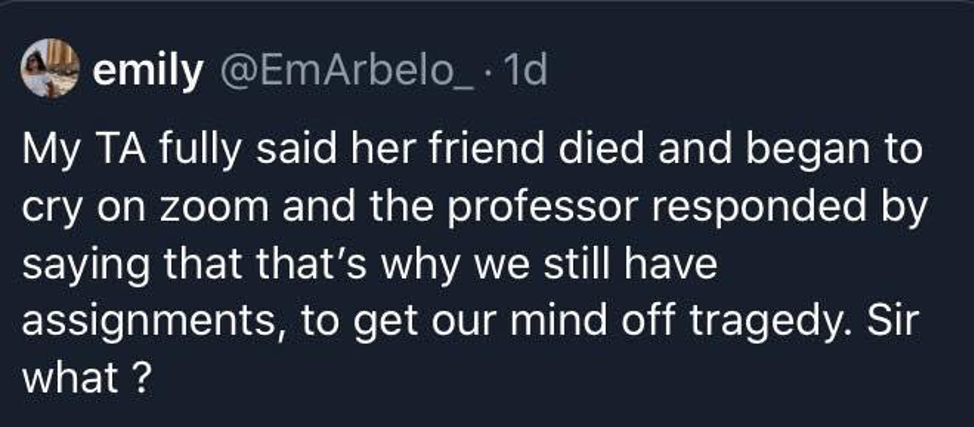

Social media is also reminding us, however, that things are NOT normal, and there are times when it is unacceptable to act as though life is normal, as this Tweet from April 7 and its response show:

Image 1. Tweet from Emily (@EmArbelo_): “My TA fully said her friend died and began to cry on zoom and the professor responded by saying that that’s why we still have assignments, to get our mind off tragedy. Sir what?” Source: https://www.facebook.com/TheProfessorIsIn/posts/2946317505414777

Within two days of being shared on Facebook by The Professor is In and commented on by Dr. Lyra D. Montero in her Medium article, “Please, Professors: Stop Pretending the Dying Isn’t Happening”, the tweet had been shared over 30,000 times and liked nearly 400,000 times. As Montero notes, the responses have largely focused on outrage at the professor for a response which shows a lack of insensitivity or empathy to the TA at that moment. While I don’t have time to do a full discourse analysis of all the responses (but would encourage others to do so), many respondents suggest emailing the professor’s dean and the school administration and/or trying to get the professor fired.

While I thoroughly agree that the professor’s response was inappropriate, in these moments I often feel that Twitter and Facebook posts, at times, prime us to react with outrage. At times we need to be outraged to have our worldview shaken. We need to express our outrage. Sometimes we even need to act on that outrage or nothing changes. Is there a point though at which our outrage turns us into a mob, a virtual (or, heaven forbid, real) band of vigilantes with pitchforks ready to end the career of someone who, perhaps, was in an unexpected and awkward situation, didn’t know how to react, and blurted out something ultimately unhelpful? Would the perpetrator, in an age without social media, simply be forgiven and forgotten?

The answer to the second question is likely yes, but the answer to the first question seems more mixed. On the one hand, the collective wisdom of half a million people suggests that this professor felt no awkwardness but should have. If the professor had been more self-aware, the Tweet would likely have been “the professor didn’t know what to say” or “the professor was silent for a minute, then continued teaching as if nothing happened.” It appears on the face of it that the professor believed the right response had been given, or at least was too proud to retract the statement in the moment. We can also read such a statement, and through Gestalt psychology, fill in the missing pieces of data, i.e. assume this is not the first inappropriate remark the professor has given in his career. All of this suggests a direct intervention with this professor is sorely needed.

On the other hand, we don’t have the professor’s side of the story or more details about the interaction. We don’t know if there are other linguistic, cultural, racial, or contextual factors driving his reaction to the TA. We don’t have enough detailed evidence to conclude that this act requires a reprimand, let alone firing. I also can find no update on the story from the original poster, which means we don’t know what action she took or what explanation (or apology) the professor may have given by now.

In contrast, Katie Cali wrote on April 8 to the Higher Ed Learning Collective on Facebook to describe her experience with students who were coping with the illness of their regular teacher:

“Today I stepped in to take over three classes for a coworker who is on a ventilator. Her poor students are now filled with anxiety and panicking. I hope I can soothe them and help them finish strong.”

There were over 800 likes, and the 66 comments were overwhelmingly supportive, offering prayers, gratitude, and thoughts of strength. While Katie’s use of the term “finish strong” suggests a continued desire on her part to see students achieve their learning objectives (or at least, achieve some learning and a sense of closure), there is a clear difference between Katie and the professor in the previous example as presented in the Tweet. By saying the “poor” students are “filled with anxiety and panicking,” Katie shows sympathy and awareness of where her students are at right now. As we read and share the experience with her, many of us see the need to “soothe” the students first, and THEN help the students to “finish strong.” While we don’t have comments from her students or audio recording from her classroom, we have a sense that she could communicate her stance to her students the way she did to her Facebook readers. This too, however, is an assumption we make as a reader.

At the midpoint on the continuum between negative and positive reactions to students coping with illness and death is this post on Twitter by Melissa Wong (@LISafterclass) on April 6 that suggests a detailed approach with a student who is (possibly) sick with COVID_19:

Student emailed me today that she is has symptoms of COVID-19 (no testing available), apologizing profusely for late assignment. Since this will start happening to many instructors, here’s a script for an appropriate reply:

I am so sorry you are sick. Please do not worry about missing the due date. IT IS FINE. I am not worried and there will not be a late penalty. We can chat about the course when you are healthy again.

More importantly: 1. Do you live with an adult who can care for you (and any children)? 2. Do you have enough food & essential supplies? 3. Since your caregiver (if you have one), will be quarantined for at least 14 days, do you have a way to get more food?

That’s it. That’s the reply you send to your student. Be human first.

This script could be modified to be a guide to also respond to students, for instance, whose parents, spouse, or grandparents are sick or who have died from COVID-19:

- Express sympathy for the illness/loss–“I’m so sorry, “my (deepest) condolences,” “I’m so sorry to hear that”.

- Assure the student that assignments can wait or be deferred, and deadlines can be extended as needed.

- Suggest additional staff who can provide support. Depending on school policies and personnel, students might have to reach out to each instructor individually, a department chair, program director, program coordinator, or academic affairs officer for further support and requirements for official requests for leave or extensions as needed. If you know who to refer to the student to, or can find out for the student, that’s a bonus.

- Assess whether the student has the resources they need. Melissa asks her student who is sick whether she has the means to take care of herself and enough food and drink to stay in isolation for two weeks. Students who have lost someone to COVID-19 might be asked if they have people in the house or online to talk to about their grief, and if they have an alternate way to mourn, as most of the normal secular and spiritual rituals (funerals, going to a church) have been disrupted. I, for example, when I couldn’t get home for a funeral of a family friend, lit a candle in my home and said a prayer at the time of the memorial service. Again, consider people on campus who can provide further assistance in this. For students whose relatives who are sick, ask where the sick person is, and whether the student has a) adequate protection if they are in the home together and b) adequate communication if the loved one is in the hospital and cannot be visited.

Granted, some teachers and professors may not feel comfortable asking students such private questions, or feel taking on responsibilities they feel is better left to academic affairs officers, counselors or social workers. In such cases, perhaps step 4 can be optional. But I would argue the first three are essential for being “human” with students during this time.

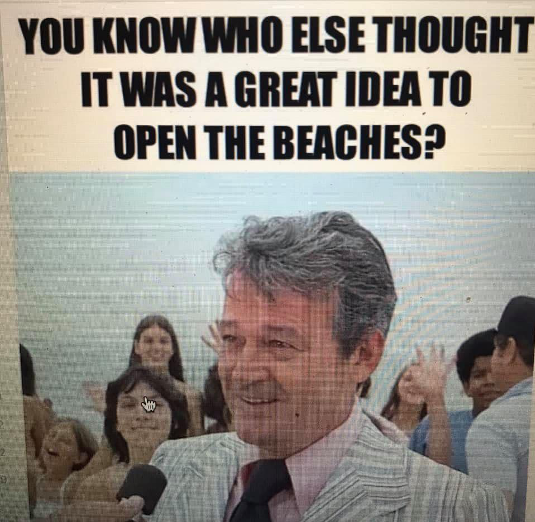

In closing my final column for this series, I want to point out that the road back to “normal” from illness, grief, and crisis is usually a long one. We should continue to work towards normal, but not go so far so fast as the mayor of Amity Island in the movie “Jaws” who declared the beaches open while there was still a killer shark on the loose in the water.

Image 2. Meme with a photo of Mayor Larry Vaughn, Mayor of Amity Island, and a crowd of beachgoers behind him from the movie “Jaws”. The caption above is his head, presumably targeted to U.S. officials who want to reopen the country in May, reads: “You know who else thought it was a great idea to open the beaches?” Source: https://www.facebook.com/kimberly.mioneaponte/posts/10221828919861668

Author Bio:

Bridget Goodman is Assistant Professor and Director of the MA in Multilingual Education Program at Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan. Her teaching and research interests include: the use of the first language (L1) in second and foreign language classrooms, language policy, and sociolinguistics in post-Soviet countries.

Academia.edu

Academia.edu